This year’s Sundance may have come to a close, but we still have a chunk of coverage to come. I mean, how could we not? Our very own Lauren Chouinard viewed every single film at the festival. You read that correctly. I repeat: Lauren watched every single film.

Absolute legend. Here are her reviews for Lucy Walker’s Camp Fire documentary BRING YOUR OWN BRIGADE, the record-setting $25 million CODA, and Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s icy WILD INDIAN.

BRING YOUR OWN BRIGADE

Director: Lucy Walker

I always chalked up California’s devastating yearly “fire season” to climate change and PG&E’s ineptitude. What I learned in BRING YOUR OWN BRIGADE was far more infuriating. At first glance, you might think this is a documentary lionizing the heroism of firefighters and efforts from community members to protect one another. Instead, this is a bleak tale of corruption, suppression, and apathy. There are brilliant scientists out there with plans to keep communities safe and stop these fires from igniting, rather than pouring money into fighting them once it’s too late. Yet, even given all the evidence of prevention tactics, community members are unwilling to sacrifice small aesthetic changes to their property, like removing gutters or measuring the heights of their bushes to make sure they’re in compliance. These are life-saving, proven ideas to protect others, yet people’s individual preferences seem to be more important to council members. And that’s just the start of it – if that doesn’t light a fire under your ass (sorry for that very unfortunate wordplay) to encourage action, wait until you hear about the greater corporate bullshit that turned our state into a matchbox that might never be reversed.

BRING YOUR OWN BRIGADEl lacks a very important part of the story: our historic exclusion of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge of their own native lands in the state fire prevention planning process. This exclusion is a crucial part of the equation that has contributed greatly to the unsustainable landscape of California, and I wish it had been addressed. For Californians who have felt the sting of our eyes from constant smoke, and a greater sting in our hearts for what our neighborhoods have lost, this film might be too rough for some to handle, but it’s an educational tool designed to encourage action and accountability from all of us on an individual and collective level.

CODA

Director: Sian Heder

CODA walked away with four Grand Jury prizes this year, and it’s understandable why from just the description alone. It’s a sweet coming-of-age tale that shows a family overcoming economic hardships and creating an accepting environment that spreads awareness of the intersections between the deaf community and their hearing family members. In a world where representation for the deaf community is much overdue, this movie checks a lot of boxes as an accessible film that not only spreads awareness of deafness, but celebrates it in a fun and light-hearted way. I love the moments when we get to spend time with everyone together as a family; the ensemble has a very sweet and uplifting dynamic.

It feels rude to nitpick a project that will be so impactful for many, and hopefully usher in a much needed disability representation, but if you were expecting a film with twists and turns, or something you haven’t seen before, this is not that. If you’ve seen GLEE or PITCH PERFECT, you know how this movie is going to flow—main character Ruby just wants to SING! We know all the characters without needing to dive in too deep; there is the flamboyant and passionate over-the-top music teacher, the shy and misunderstood love interest who she gets paired to do a duet with, and the quirky parents who live to embarrass their children. The moment Ruby started singing “Both Sides Now” in a rehearsal (one of my favorite songs of all time), I knew the movie was going to end with her eventually signing the song to her parents in her Berklee College of Music audition. Typically, this kind of predictability in movies targeted toward young adults can be pretty vomit-inducing, so I was delighted to see how well received it was. Its light and airy tone is the uplifting spirit we need right now in a pandemic, and probably a welcome sight for many festival goers after bleak films like WILD INDIAN or ON THE COUNT OF THREE. This is the kind of movie you can watch with your family that makes you want to hug your mom, and if that was what Sian Heder was going for, then mission accomplished. Have fun on Apple TV+, CODA!

WILD INDIAN

Director: Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.

WILD INDIAN begins with a man covered in smallpox blisters and a quote: “Some time ago… there was an Ojibwe man who got a little sick and wandered West.” This is where the metaphors begin for a film that relies on parables to tie everything together. Smallpox was brought to American Natives by white colonizers centuries ago, but under the skin, you see the effects of colonization reverberating through Indian Reservations to this day, whether it be via widespread addiction, Christianity, or an unlisted trauma. When we meet Makwa, he is suffering from extreme abuse at home. His stoic anger boils over from the moment we are introduced to him, and only grows deeper and more frightening as the film goes on. He kills one of his classmates in cold blood, seemingly for no reason at all; I wish this could be explained more than just “hurt people hurt people.” There are lots of traumatized kids out there who don’t bury bodies, piss on their shallow grave, and flee. Ted-o, Makwa’s friend, witnesses this brutal murder, hiding the painful secret for decades.

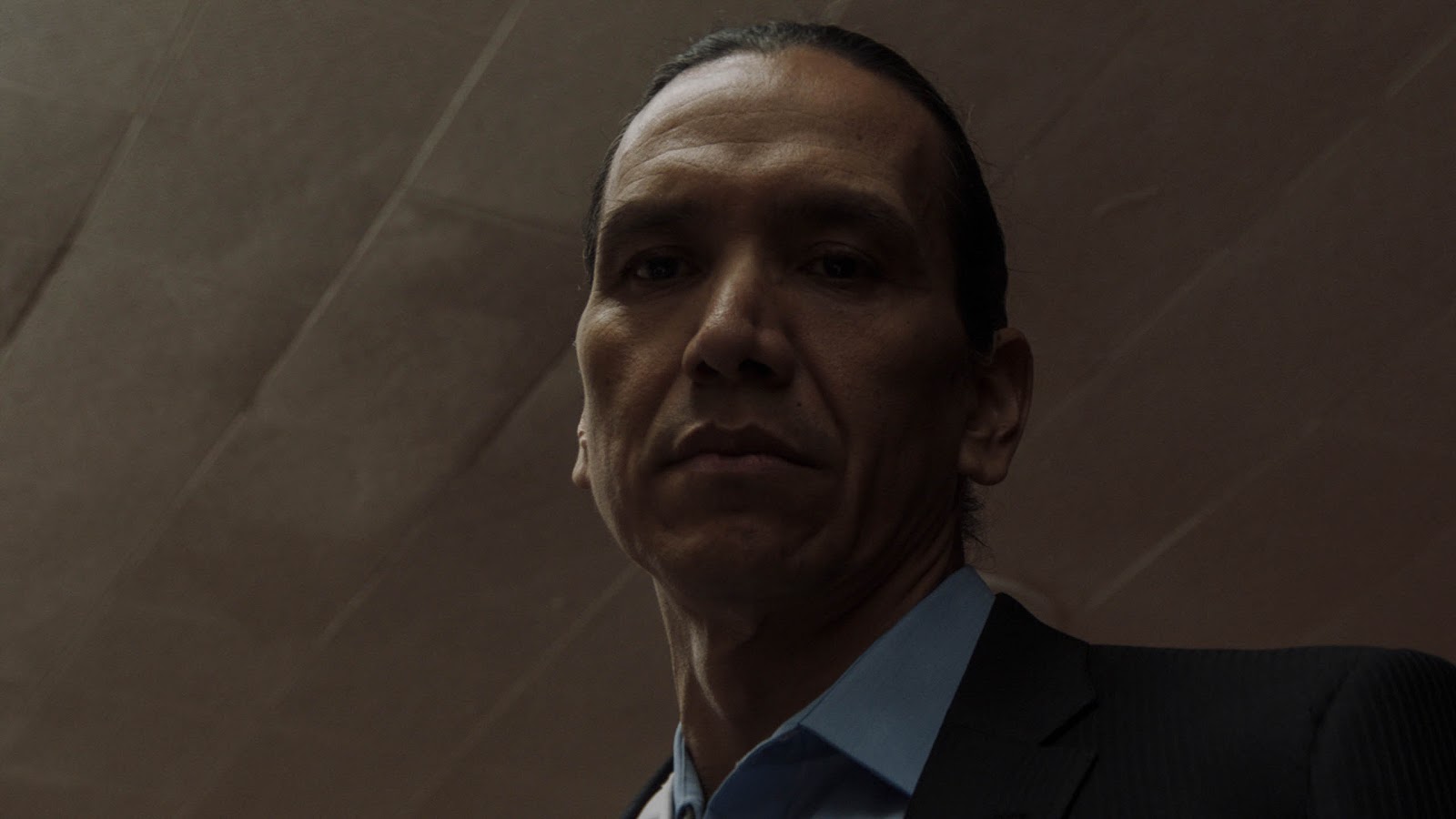

Flashing forward to the duo’s adult years, WILD INDIAN jumps to how differently the two have grown up. Ted-o, played brilliantly by actor Chaska Spencer, stays on the reservation until he is booked and jailed for several years on drug charges. He is covered in tattoos representing his tribe and spirit guides, wearing his culture outwardly and proudly. Despite falling into the negative traps so prevalent on many reservations, Ted-o serves as a moral compass throughout the film. He has a conscience he continuously wrestles with, trying to do the right thing in order to bring justice to his murdered classmate from decades ago. Countered to Ted-o is Makwa, whose journey couldn’t be more different. Makwa continues to run away from his upbringing and adopts all the trappings of a Eurocentric white-American standard of modern “success.” He changes his Ojibwe name to an Anglo-Saxon name and marries a blonde, blue-eyed woman. He strives for the large modern style home and the high-paying corporate job, of which his trauma-induced Patrick Bateman-esque sociopathy is probably well suited for, yet he cannot change the color of his skin or erase how the world sees him, leaving small hints of his culture that others can easily digest. We see him reject his own history and past throughout the film, hating his own people, and hating himself—using the image of his culture only when it suits him. Makwa surrounds himself with white characters, and he deliberately uses his size and cultural statements to intimidate them. He thrives on feeling as if he has power over these people, as if he were reclaiming the narrative of the conquerors versus the conquered. These white characters, (played by actors with bigger names and clout in Jesse Eisenberg and Kate Bosworth) exist not as fully-formed people, but as metaphors for whiteness and privilege as a whole. It’s an interesting perspective, especially as Native Americans have historically been reduced to metaphors for natural mysticism and barely as fully-formed human beings with light and darkness inside of them.

During the Q&A for WILD INDIAN, one viewer asked if the team felt pressure to write Indigenous characters differently, due to their historic lack of positive and accurate representation throughout film history. Lead actor Michael Greyeyes was quick to bring up the point of how cognizant he is of how Hollywood writes indigenous people, and how audiences might absorb and project those images outward. However, he felt unafraid to challenge himself as an actor in this role, not feeling as though he was representing all Indigenous peoples, but one example of how trauma might affect a person growing up in those circumstances. In portraying such a sociopathic character, he found that he was able to reclaim and re-contextualize this grotesque portrayal on his terms. Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. remarked that he did not set out to write a story about positive or negatives, but just a story about two people. I understand and respect the yearning for juicier and more complicated roles, but Makwa is truly such a despicable character that it’s hard to see him as anything other than a monster by the end of the film. I worry this may not play as expected to more mainstream audiences, especially those with limited knowledge of Native American culture and the obstacles they have to overcome. For all its issues and all its darkness, I am still proud of Corbine for creating such a detail-oriented and well thought out debut. I want to see more of his culture on screen in the future— only next time maybe with a little more tact. It was difficult having to watch this parade of broken bodies, but perhaps it’s most important that I feel that discomfort, and try to synthesize those feelings into real life action.

Comments