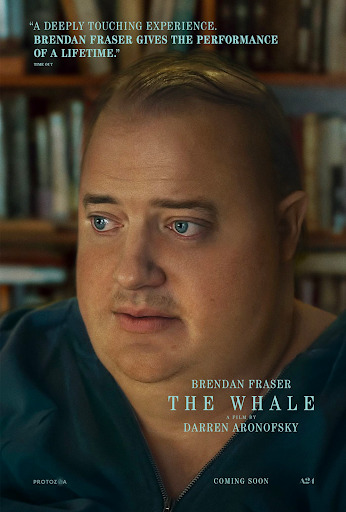

It’s the still that launched a thousand ships: Brendan Fraser in his comeback as Charlie in Darren Aronofsky’s THE WHALE. In lieu of a trailer, promotional materials, a proper poster, A24’s campaign for the film hinged on… A singular still.

The Still: no really, this is the real poster.

The fact that this worked (somehow) is beside the point; having seen the film, it’s a shock A24 even let a still see the light of day. Nothing in the film is marketable, so it’s no wonder the film let Fraser’s admittedly-great comeback performance do the heavy lifting.

If only he could have lifted something worthwhile.

Aronofsky’s film tells the story of Charlie (Fraser), a reclusive, obese English teacher who in the midst of a life crisis attempts to reconnect with his estranged daughter (Sadie Sink). There are very few people who break up the solitary monotony of Charlie’s life. Hong Chau’s Liz serves as both his physical caretaker and only social support, the same pizza delivery driver (Sathya Sridharan) drops food off every day, and LDS missionary Thomas (Ty Simpkins) stops by every so often to evangelize. His apartment is as gray and drab as you’d expect given the depressive nature of his existence, merely serving as a context under which Aronofsky and screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter (adapting from his play of the same name) present their meditations on suffering, religion, trauma, and confession.

It is, of course, impossible to talk about THE WHALE without discussing the conversations of fatphobia swirling around it. Fraser wore a prosthetic fat suit for the role on top of a substantial real-life weight gain, a choice that feels cartoonish and outdated at best. So much of the film relies on Aronofsky channeling body horror (as is the only thing, seemingly, he knows how to do) from Charlie’s eating, his wheezing, his movement. The whole thing is such an immense caricature that it’s hard to even mine the fatphobia conversation in the first place. Aronofsky’s vision of Charlie borders on the supernatural, practically begging you to feel disgusted by him over and over and over again. His fatness is at once central to the film—because of how heavily Aronofsky leans into the grotesque—and trivial to the story’s core themes. Any number of ailments or signs of deterioration could have taken its place and very little would change (in the vein of Miss Havisham or Quasimodo).

Instead, we’re left with a caricature of a person whose presentation can best be described as tasteless; frankly, the conversation of fatphobia doesn’t even scratch the surface of the lack of humanity and empathy Aronofsky affords Charlie in general. The same could actually be said for any of these characters: they’re outlines of people, half-baked gestures at some great literary Thing. Ellie, his daughter, is nothing short of demonic, the worst toddler you’ve ever met scaled up into the teenage world with access to Facebook. Thomas is a mouthpiece for Aronofsky’s exploration of religion, which was already tired in 2014’s NOAH. And Liz seems to exist only to respond to other’s trauma; she’s a walking sob story whose humanity is defined not by anything about her (despite Chau’s best efforts) but by the losses she’s experienced throughout her life.

Moreover, THE WHALE fails to elevate its theatrical origins. Aronofsky sparingly takes advantage of the cinematic medium and instead seems content to simply record the play. The grand monologues and heightened emotional presences that may very well have worked in a stage production don’t ring true here. It’s as if the bones of the story are forcing us to feel close to these characters, but the film itself denies us the opportunity. Emotions are ever-present but rarely earned. Orchestral swells loudly announce tearjerker moments. Any semblance of subtext is spelled out for you in no uncertain terms. Multiple literary metaphors, chiefly the titular comparison between Charlie and “the whale” Moby Dick (lol) are hammered into the audience’s minds incessantly.

The whole thing puts a damper over the central appeal of the film, which is of course its role in the Brenaissance. Barring his role in DOOM PATROL, Fraser’s career has largely laid dormant following his 2018 allegation that then-HFPA-president Philip Berk assaulted him in 2003. So naturally, seeing him come back in such a major way is noteworthy. The work he does in the film is some of the most emotionally honest in recent memory. If there’s one thing that anchors THE WHALE, it’s the earnest commitment Fraser exemplifies, even as Aronofsky’s direction and Hunter’s screenplay seek to undermine it with triteness. I’d say the film doesn’t deserve the amount of heart Fraser puts in, but the disconnect between his work and the film itself begs the question of why he took this role in the first place.

Watching THE WHALE, you get the impression Aronofsky just isn’t capable of actual empathy. Throughout his career, his best work—BLACK SWAN, components of MOTHER! and REQUIEM FOR A DREAM—succeeds because of a lack of groundedness. Those films are unsubtle, but they’re also spectacles: surely no one is demanding quiet nuance from the same film where Natalie Portman scrubs a lipstick-scrawled “WHORE” off the mirror.

But a film like THE WHALE requires nuance, subtlety, quiet—and rather than let us arrive there on our own, Aronofsky seems happy to strong-arm tears out of us.

The worst part is that somehow it’s working.

Comments