There’s a truism that art is theft. MADE IN HONG KONG embodies this on the level of the physical—it was filmed on discarded scrap—made with about 40,000 feet of leftover 35mm stock and arriving in American theaters 23 years after its frenzied creation. The movie—and this is a compliment—feels stolen. The productive tension of the movie comes between its physical and spatial energies—writer-director Fruit Chan cramps his characters into tenements as his edits speed through time, with a roiling pace that only folds into tragic when we realize it is not going anywhere. There’s not much more than three or four primary locations in the film—largely the cramped tenements of the characters, or the Hong Kong night-scapes caught on the fly—but they are consistently revisited, revitalized with new textures.

The film’s drama begins with the suicide of a young teenager, Susan (Amy Tam Ka-Chuen)—flinging herself from a daytime rooftop, ultimately found by a disabled young Triad, Sylvester (Wenders Li). Sylvester is crewed up with protagonist and fellow Triad “Autumn Moon” (Sam Lee) and their terminally ill friend Ping (Neiky Yim Hui-Chi). Moon and Sylvester initially harass Ping over her family’s debts—they’re erstwhile bookies—but that business slowly gives way to intense loyalty, flirtation even, as Sylvester and Moon stall on what to do with Susan’s suicide note, and the three weave through the streets of Hong Kong. The three are something of a mirror of Nicholas Ray’s dejected old youths—the oft-cited comparison is the co-dependent trio of REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE, and if memory serves right, this movie seems to capture that one’s simmering sweetness, too. They are entropic but electric, stupid with words yet wise in between them. They accelerate each other’s energy; the audience enjoys their pleasure on a minute-by-minute basis, perversely knowing what that pleasure will curdle into. These kids are subsumed by their surroundings, and so they subsume themselves into Western pop culture. Their collected VHS tapes inform the values; the values inform the behavior; the behavior seals the destiny, and not anywhere we want to go.

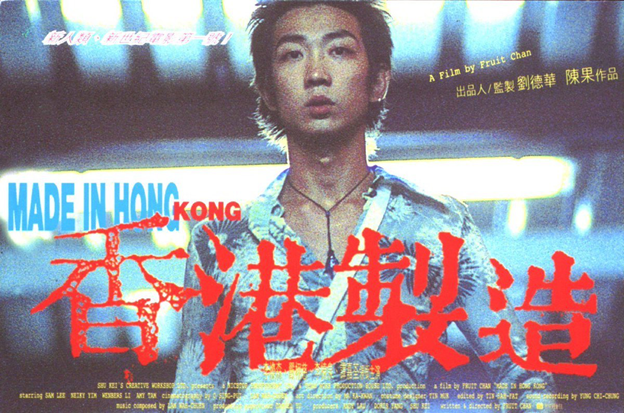

Protagonist Moon (Sam Lee), framed in the original 1997 poster

The actors are largely unprofessionals: young, plucked from backgrounds more leaning towards fashion than film. I mean this in the best way: it shows. Chan directs them with special attention to the body, and the details that linger longest are often the physical: Ping pursing her lips, Sylvester’s sweetness and speed. Moon in particular is framed with a luscious, gawky grace—hips jutting out of his crop-tops. The movie puts a gun in a sexy boy’s hand and still has the formal grace to insinuate that it’s ridiculous. It’s a reverse coming-of-age tale in the sense that the deeper the characters tunnel into themselves, the farther from grace or actualization they are. Moon is a hell of a guy to hang a movie on, a classic New Wave chump: chest puffed out at the wrong time, retreating into cowardice at the wrong one, too. Chan’s direction both guides his energy and manages (like the Truffaut guy did!) to chastise it—to suggest that there is a better way. There’s a scene where Moon follows his estranged father and nearly hacks him to death—until he sees ANOTHER estranged son hack his father to death; the strange, surreal symmetry of that is going to haunt me for years.

Characters’ exteriors and interiors are fused into each other, brilliantly

MADE IN HONG KONG riffs through its locations again and again, varying in speed and color, mounting in expressiveness and fatalist dread—a faster if no less claustrophobic riff on the stylings of Edward Yang. The picture’s fixation on patterns is no accident; suicide is returned to, again and again, like a cosmic loop. Susan’s suicide can be scanned as the original sin that incites the drama, unifying the protagonists’ obsessions; one could also clock it as the end-game—the logical conclusion to the characters’ tunnel vision. It can be read as momentum; it can also be read as denial. Chan’s script is to be commended for its ruthless clarity proceeding from Susan’s suicide. I’ve never seen a Fruit Chan film before, but he is an astounding writer-director in the sense that he understands that those objectives naturally work against each other. Fruit Chan’s screenplay is carved out of certainty, fate; Fruit Chan’s direction stems from chaos, disorder. The experience of watching MADE IN HONG KONG is the thrill of these dueling prerogatives; they work in opposition until they totally, tragically do not.

Comments