In case you haven’t heard the news, political correctness killed comedy. My apologies, folks, no one is allowed to be funny anymore, lest we offend! Any brain-hemorrhaged homunculus with a long-form casual discussion podcast and an unpublished, 42-page essay on HORACE AND PETE is game to compare their plight of being ruthlessly called out for making gay jokes to living in a totalitarian state, but their opponents lately have been pointing to a recent film that disproves all the anti-PC bullshit. Enter Taika Waititi’s JOJO RABBIT, the breakout hit of TIFF 2019 and the high-profile return of a certain brand of Mel Brooks-style comedy deemed too risky by the modern climate about a little Nazi boy who grows up by learning that being a Nazi is bad. Waititi, no stranger to owning up to a challenge, is armed with a post-Marvel blank check and a healthy stock-pile of THOR: RAGNAROK money leftover just in case this doesn’t work out, but his limp efforts curtail every moment of JOJO RABBIT, a film that, funnily enough, so many ran to the defense of when the fabricated “Disney is so worried about JOJO RABBIT that they may pull it” news story got circulated; little did we know that this would feel made in tandem with them from day one.

Cool, dude

Belief systems are born with holes poked through them: prodding yields some solid satire, but there’s a widespread psychological defect left unscathed by merely making fun of them. Worthwhile satire ribs, for sure, but it’s destructive—it is demolition and renovation in one. Rarely does the mockery aim for the proselytized. JOJO RABBIT skewers the product, what with its legion of doofus, gun-loving Nazi officers (one of the few good, premise-fulfilling jokes in the film is when Jojo is nearly assigned to “walk the clones”) running about until they meet a noble off-screen death, but imparts zero indictment of the buyer: of Jojo, of the Nazi youths, of the German monsters who welcomed the National Socialist Party with open arms. The opening credits are especially puzzling. Sure, realizing that the German-sung version of The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” is actually performed by The Beatles and not a cover band is an incredible new bit of trivia to keep in my back-pocket, but the sequence itself, the song playing over vintage propaganda of fanatic Nazi sympathizers treating the encroaching Führer like The British Invasion doesn’t play well.

Yes, I know, Reader Who’s Hungry To Explain Satire, the audiovisual juxtaposition of both creates new, ironic meaning, but the commentary eats its own tail when the proceeding film sincerely partakes in this uncomfortable cheeriness that all too well mimics the intoxication of indoctrination. There’s a whole lot of Nazi sympathizing in this “anti-hate satire” y’all done made here. There ain’t a single mean bone in JOJO RABBIT’s body, an alarming red flag that has somehow also become the nucleus of most of its praise. Here’s a solid reminder as we enter the 2020s: it is okay to be mean to Nazis. The rehabilitation of hate is a thorny topic, one with no clear beginnings or ends. That is, unless you take notes from JOJO RABBIT, wherein getting past embedded prejudice for the Jews is as simple as sleeping off chicken pox. Chicken noodle soup for the soul cures all ailments, Nazism included.

You’re an antisemite? Nothing a few chuckles with your pals won’t fix!

You could argue that this is JOJO RABBIT’s child-like POV at work, the only way for any of this subpar Wes Anderson nonsense to be borderline acceptable, but to say so sure underestimates the emotional depths of maturation. Waititi made a film about a child, a major difference from making a film through the eyes of one, and he’s workshopped a child who’s a complete bore. Roman Griffin Davis is handed the major task of carrying the entire film, and he does well enough, bolstered by the director’s impressive track record with young lead performances, but there was never a moment, not even in Jojo’s redemption arc, where I didn’t want to yeet this little Aryan brat out a glass window.

Considering this played the same festivals as the marvelous PARASITE, and is currently in theaters at the same time, I’m surprised the hammer hasn’t been brought down on how this hard-stops and starts its genres. Gear-shifts from surreal comedy to sentimental family drama then back to semi-serious Holocaust picture guarantee whiplash. The true fun of shock satire is not knowing when to giggle. It’s a duet: the film performs a high-wire act while the viewer is forced to walk on eggshells—you may want to laugh, but how hard and how loudly? The comic bits in JOJO may as well be accompanied by a neon “LAUGH!” sign. By the time we reach the conclusion of the film’s jolty, sullen third act with a dance sequence that’s been threatened multiple times, our characters have made so many third-rate Dad jokes at inopportune moments and, in the process, missed out on dozens of other savage gags.

As a whole, I honestly don’t know what Taika is trying to achieve here. A filmmaker can push “love” all they’d like, but it will often end with them backing into the steel bear-trap of producing a feel-good film that celebrates complacency above all else—any delighted viewing of JOJO RABBIT should be accompanied by a mandatory viewing of Rossellini’s GERMANY YEAR ZERO the second after JOJO’s fade to black. Waititi’s film is a minor set of re-writes away from being an irreparably harmful, pop-fascist masterwork. That sort of danger often spells gold for satire, but in the case of JOJO RABBIT, it’s suggestive of more of the 2010s’ thoughtless, counter-productive optimism, as if showing up to rebel frontlines with nothing but a stack of Redbubble stickers is going to save a life.

Sometimes, it’s okay to let a darling die and stay dead

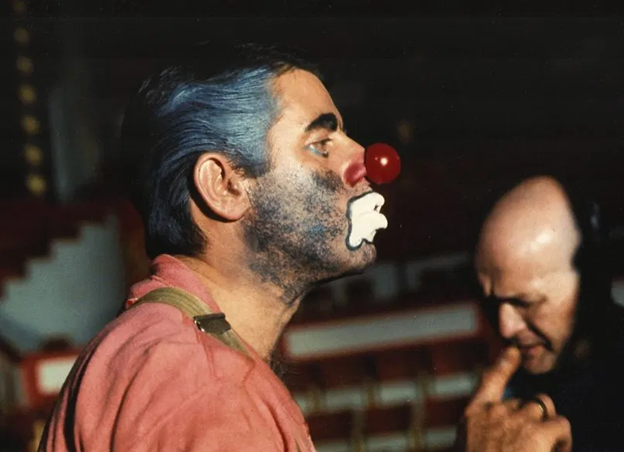

Leaving JOJO RABBIT, it wasn’t difficult to think of films of a similar ilk with more immediacy (AKA filmed and released during the Fall of Berlin immediate), more fury, and more bravery—your THE GREAT DICTATORs and TO BE OR NOT TO BEs. Yet lingering in my mind was a film that never saw its release. The late, great Jerry Lewis was his own biggest fan, a consummate entertainer followed by his own personal marquee, just in case the building he entered didn’t have one—there was nothing he valued more than his own work, and yet to this day, THE DAY THE CLOWN CRIED remains securely under lock and key. Lewis’ Holocaust dramedy, following a Jewish circus clown who finds meaning in his life by distracting captive Jewish children before they enter the gas chambers, was deemed so heinous by the director that he only ended up begrudgingly showing it to a select few. Famed comic actor Harry Shearer was one of those few. “This movie is so drastically wrong,” Shearer said, “its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.”

Lewis’ lost film ends with The Clown entering the gas chamber himself, having lived a life without children of his own until the Holocaust gave this lonely clown his most receptive and gracious audience. Lewis in 2013 at Cannes, yes, the same press tour he doubled down on his regrettable sexism, said of the film that “It was all bad and it was bad because I lost the magic. You will never see it, no one will ever see it, because I am embarrassed at the poor work.” Waititi could have stood to heed such sage advice; JOJO RABBIT should’ve been shuttered before it ever had the chance to conceitedly gallivant about awards season with a high-and-tight and nothing to its name but a bucketful of rotting middle fingers.

Comments