Thanks for clicking into our end of the year coverage! Merry-Go-Round Magazine is an independent culture site funded by people like you! If you’re enjoying our End of 2024 Coverage, consider becoming a member of our Patreon, or even donating to our operation here! Between now and January 1st, you can get one of our amazing crewneck sweaters if you become a Patron at the $5 tier! Thanks in advance for supporting MGRM!

The horizon is hazy. In late February of 2025, and with an awards season more elongated than ever, every fandom, standom, and even just casual cinema enthusiasts are still collectively dead-set on the cinema of 2024: We can blame the release calendar (once again, studios are slipping into the nasty habit of leaving major weekends empty, only to cram all of their end-of-year product into a tight 60-day holiday window), but I have a feeling the next few years are going to keep having us looking backwards for some peace. Without any further ado, here are the 24 best films we at Merry-Go-Round watched in 2024.

24. JUROR #2

Director: Clint Eastwood

It’s odd to call Hollywood stalwart Clint Eastwood an outsider, but increasingly the nonagenarian filmmaker feels like an aberration in the film industry: a studio-financed director whose straightforward, understated dramas couldn’t be further from the hyper-corporate, bloated IP that companies like Warner Bros. and Disney have been producing en masse for the last decade. His latest, JUROR #2, was almost sent directly to streaming on Max, and it seems purely by accident the film found its way to theaters in a limited release—all the stranger when considering JUROR #2 is not only a new Clint Eastwood movie, but the sturdiest and most engaging Clint Eastwood movie of the past 20 years. Eastwood’s longtime distrust of institutions fits seamlessly into JUROR #2’s depiction of the American justice system, which follows Nicholas Hoult’s Justin Kemp as he squirms between trying to convince his fellow jurors the accused may be innocent while avoiding being discovered as the possible manslaughter culprit. Due credit should also be given to screenwriter Jonathan Abrams, whose script meticulously escalates the moral dilemmas Kemp and the people surrounding him go through at every possible turn. It’s a further testament to the film’s success that—despite all the gray—there is no doubt that Kemp is in fact guilty. Nicholas Hoult gives a career-best performance, where so much tension is built purely through long close-ups as he struggles to contain his reaction to every new argument or piece of information. Equally important is Toni Collette as prosecutor Faith Killebrew, who warms to the possibility of the defendant’s innocence. Kemp and Killebrew importantly go on reverse paths through the movie: Kemp ultimately chooses himself and his new family rather than freeing an innocent man, whereas Killebrew comes to realize the truth is more important than her personal ambitions. The silent confrontation that concludes JUROR #2 ultimately shows how our justice system creates deadlocks that do not allow for negotiation and always cost someone more than they deserve. [Ethan Cartwright]

23. UNION

Director: Stephen T. Maing, Brett Story

Since the rise of neoliberalism, coupled with mass deindustrialization, America’s once-formidable labor movement has withered into a fragile husk. Gone are the days of rounding up the factory to joust capitalist pigs. Despite the rapid expansion of the working class, today’s proletariat are paradoxically depoliticized. So, what happened? Stephen Maing and Brett Story’s UNION offers some insight. The film spotlights a group of workers led by Chris Smalls as they successfully unionize at an Amazon warehouse, one of few Western companies with domestic operations. While the company is subject to national labor and wage laws, there have been many reports of Amazon partaking in comically evil schemes to suppress worker power and maximize labor power, all within the narrow confines of legality—allegedly. UNION transforms these accusations of corporate tyranny into damning, concrete evidence. In the Vérité tradition, Maing and Story recede behind the camera—although, both directors were quite involved in solidarity organizing—to observe the Amazon Labor Union’s (ALU) linear trajectory, from grinding for support to winning tenuous recognition. But UNION also showcases how fucking difficult modern unionizing can be, how organizer egos can swell and burst, how sectarian schisms spontaneously manifest, and how energy can deflate midway through this uphill journey. In such moments, the film makes it strikingly clear that our neoliberal structure is programmed to crush worker solidarity. The ALU’s final victory feels like a lucky anomaly, a systemic oversight, rather than a universal possibility.

Indeed, in this era of political nihilism, it would be terribly disingenuous if UNION replaced its messy textures for feel-good agitprop. The film’s unflinching stare at the good and the bad—the real and the ideal—calls to mind Barbara Koople’s gaze in HARLAN COUNTY, USA, a documentary covering the Kentucky mine workers’ strike. In the end of HARLAN COUNTY, miners attain a satisfactory contract and optimistically return to the field. Little did they know that 50 years later, neoliberalism would erase all union mines in the region. UNION also concludes in ecstatic release. But unlike Koople, Maing and Story have the realist foresight—hewn from surviving finance capital—to doubt the ALU’s fairytale ending. Collectivizing is merely the first step, they tell us: The real test lies in how workers will defend their hard-earned organization from a viciously inhumane system intended to raze everything for their profit-prophets. [Vicky Huang]

22. A REAL PAIN

Director: Jesse Eisenberg

Much to my mother’s dismay, I’ve been adverse to reconnecting with my extended family for several years. Not for any deeply negative reason. Just an overall feeling that those relationships, particularly a specific cousin who I was once close with, are built on superficial obligation and nostalgia. I find him hard to talk to whenever I try, so I’ve just given up. These are the deeply embedded layers of Jewish familial guilt that I brought into A REAL PAIN—Jesse Eisenberg took care of the rest. Showcasing a remarkable command of tone throughout this tour through Poland, particularly for only his second feature, this could’ve easily been a one-note travelogue where he and Kieran Culkin yuck it up while taking in local landmarks and dives. Culkin’s Benji acts as a stick of dynamite thrown through this formula, the unpredictable cousin who can make or break a vacation day depending on his shifting mood as he copes with the loss of his grandmother throughout this tour. Sometimes he feels spry enough to flirt with the group’s lonely divorcée (Jennifer Grey) or pal around choreographing pictures around statues of fallen soldiers. At other moments, he’s overcome with guilt at the very thought that his ancestors who stood on the very ground he now leisurely wanders found themselves victims to a genocide that he can only fathom. Eisenberg doesn’t outwardly coddle or shame this behavior. He allows his character, David, to express both enjoyment at getting these wayward days to reconnect with someone he cares deeply for and exasperation at Benji’s outbursts.

The personal journey they go on, and the place where their relationship ultimately lands, allows the audience to decide where they fall on Benji (though regardless, he’s likely made them laugh). Culkin’s thorny delivery, perfected on SUCCESSION and re-oriented here, is seasoned enough to bring any punchline home. These types of stories are vital for men; we’re so inundated with films where we betray, bully, or kill each other. If they are about family, they often end in explosive crash-outs in the name of getting some character actor their long-overdue award. Rarely are they allowed to simply flow through different emotions, some joyful and some painful, and come out on the other side with bonds still intact. A REAL PAIN will last because whenever some guy happens across it on streaming, they just might make a call that could heal something within them. [Michael Fairbanks]

21. CHIME

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s CHIME—the first of three new releases he had last year—clocks in at just under 45 minutes, and packs more dread and darkness in that runtime than most horror filmmakers are capable of in their entire careers. Kurosawa’s return to the style and genre that brought him international acclaim in the late 1990s is a relentlessly stripped-down, abstract work. Earlier Kurosawa films would have some sort of supernatural disjuncture occur and slowly take over the world of the movie, whether that be the amnesiac manipulator behind random murders in CURE or the ghosts haunting the Internet in PULSE. CHIME, on the other hand, takes place in a world where that disjuncture has already spread everywhere. Throughout the film, everyone seems disconnected from everyone else and from their own emotions. The main character, Matsuoka (Mutsuo Yoshioka), teaches a cooking class and explains to a detective that the lessons often work to distract students from the outside world, hinting at the abundant need in today’s world for disassociation from everyday life. Nevertheless, a student kills himself during the class after insisting he keeps hearing a chime (like a “metal scream”) and that part of his brain was replaced by a machine. The violence of the suicide seemingly affects Matsuoka into murdering another of his students during a one-on-one session, after which we witness him methodically dump her body in the woods. Kurosawa echoes the palpable sense of disassociation in how CHIME is staged and shot: The horror of the movie never comes from any images of ghosts or monsters, but from empty spaces and complete stillness turning into sudden movement. Everyday sounds are louder and sharper, to the point where aluminum cans being dumped into a trash can becomes unbearable or Matsuoka slurping his coffee translates into an audio jump-scare. The abstraction in CHIME ultimately addresses our own disconnect and isolation; the fear of a world where institutions are crumbling and people are becoming more desperate and violent against each other. By the end of the film, Kurosawa effectively makes every location seem haunted and every person just as capable of random violence as Matsuoka. [Ethan Cartwright]

20. DIDI

Director: Sean Wang

Sean Wang’s directorial debut DIDI captures the final moments of ubiquity in a historically idiosyncratic youth culture. This small paragraph will likely read as “old man yells at cloud,” but as we’ve watched the zeitgeist meaninglessly expand and flatten out over the last 15 years and helplessly experienced the monoculture slowly die, every coming-of-age tale that will come out of this era will be forced to use historical tent poles to frame stories—and, it should be noted, the way we’re moving socially and politically, there will likely be a LOT of those tent poles for minority groups in particular to frame stories around. But DIDI is just a story about a kid trying to figure out who he is entering high school. Wang’s semi-autobiographical story captures what it was to be a teenager during the emerging internet era with a wit and acuteness that feels universal; DIDI frames a relatively brief period where your awkward adolescence was defined by pinned MySpace songs, AIM away messages, and mastering T9. If that period feels nostalgic, it’s only because what came after it has slowly lost any and all definition—the things that would come to replace those fleeting tenets, like Facebook and iPhones, haven’t gone away in literally a decade-and-a-half. At the emotional core of DIDI is Wang’s first-generation immigrant experience, following 14-year-old Chris as he navigates racist microaggressions from his peers and an understanding of his relationship with his Taiwanese mother (played by Joan Chen, who should have gotten significantly more awards buzz). Through it all, DIDI makes this experience feel just as culturally pervasive as any other detail in the film—an experience that, unlike the setting, is itself timeless. If we fast forward even three or four years to the early 2010s, will entering freshman year of high school have any kind of nostalgia to it? [CJ Simonson]

19. GASOLINE RAINBOW

Director: Bill Ross, Turner Ross

When people throw around “cinéma vérité” these days, they’re often describing technique and aesthetic—they’re referencing, in technical terms, the way the camera moves around a space, or honing in on a kind of documentary-style naturalism that has bled further and further into narrative fiction in recent years. But when I say that the Ross Brothers tap into the cinéma vérité tradition with their films, I’m not so much referencing the nature of the camera—though that is true—but instead the definition as given by the French: “Cinema of Truth.” With GASOLINE RAINBOW, their first acknowledged fiction feature, they seek to find the quiet pain of modern adolescence, innocence, and transition. We follow a group of recently graduated teens traveling from a rural Oregon town to the Pacific coast, a journey that begins aimlessly and only eventually finds purpose circumstantially because a group of similarly wayward youth mention “The Party at the End of the World” somewhere near Portland. That narrative quietly reveals itself both to us, to the filmmakers, and seemingly to the characters; each scene reveals a new discovery or epiphany—small “core memories,” as these Gen Z’ers would call them, flawlessly display the highs and lows of being young, from having your van get stolen to spending all night at the skatepark with strangers. Like BLOODY NOSE, EMPTY POCKETS before it, this verisimilitude gonzo filmmaking finds a truth at the core of the story, even if it’s not the truth. In Tony, Micah, Nichole, Nathaly, and Makai, the Ross Brothers provide us a glimmer of timeworn hope for the future in a present that remains very bleak. [CJ Simonson]

18. LOVE LIES BLEEDING

Director: Rose Glass

My friend worked on the beginning stages of production of LOVE LIES BLEEDING, and before I saw it, he told me, “This movie is made for a very, very specific kind of person.”

Turns out, that person is me.

It hypnotized me with its relentless, sweaty, unhinged energy and atmosphere so suffocating you feel like you need a shower afterward. Rose Glass directs the Hell out of this thing, leaning into surrealism without ever losing sight of the emotional core. It’s sexy, it’s violent, it’s over-the-top in the best way possible—a neon-lit, blood-soaked fever dream that oozes style and doesn’t so much unfold as it does spiral, careening from one wild moment to the next. It’s the most fun I’ve had in a theater all year. Katy O’Brien is an absolute revelation in this; not only is she absurdly hot as a muscle mommy, but her performance has such raw depth and intensity that I felt like I was watching The Devil and God raging inside her at all times. Her presence is magnetic, shifting effortlessly between vulnerable and terrifying. Additionally, Kristen Stewart was born for a role like this—you can tell she’s been frothing at the mouth to play a character this grimy and feral. She nails it. Her Lou is equal parts hardened and heart-wrenching, a wounded figure caught in a love story that burns through everything in its path. The sheer visceral power of LOVE LIES BLEEDING makes up for any narrative shortcomings. Some people are going to hate it. Some are going to be confused. But for those of us tuned into its frequency, LOVE LIES BLEEDING is a feral, thrilling, sweaty masterpiece. It’s the lesbian GOOD TIME, BOUND on ‘roids, THELMA AND LOUISE if it was kissed by David Lynch, but above all, LOVE LIES BLEEDING understands the seductive power of loving someone so much you’d burn the world down for them. [Lauren Chouinard]

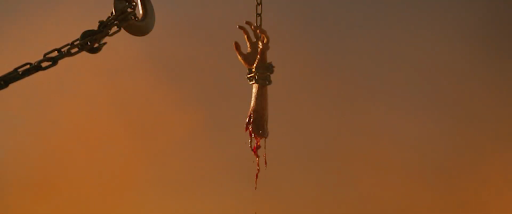

17. FURIOSA

Director: George Miller

FURIOSA follows a narrow path of Odyssean vengeance where social stature becomes part of the art of war. The ways in which Furiosa is perceived (i.e. lecherously, valiantly, submissively), how she decides to perform on these conceptions of a woman in the wasteland, and the positions of power she seeks to attain through how she is seen are three mental prisms she shackles herself to in ultimate pursuance of an epic act of inarguably righteous, retributive violence. Water’s wet, the sun is hot, and you plant Eden’s peach tree in your mother’s killer’s groin then seize your dead rapist boss’s Citadel. Duh. Admittedly the little sibling to FURY ROAD’s pantheon of chaos, the final chapter in Miller’s MAD MAX saga instead luxuriates in a simmering pot of juices more than 40 years in the making: the opportunity to revel in a world where “Piss Boy” is no mere nickname, but rather a functionally professional title. It’s not a stunt-a-minute extravaganza, nor is this dense prequel that opens with a gloriously droll 25-minute chase scene particularly breakneck, but FURIOSA invites you to something fuller… Something hearty and rich and maybe even too filling. It’s a film that melds digital and practical image-making to best capture the vivacious imagination of its creator, everything carved out of a dream. The imagery ranges from George-Lucas-prequel-level phony to classic hands-in-the-mud Ozploitation, nothing ever veering from Miller’s most absolute intentions. It’s a film where anything and almost everything happens, and it’s in service of breathlessly explaining… Systems of commerce in the post-apocalypse. Just awesome. It feels like exactly the movie George Miller wanted to make.

Even Miller’s sound mix is unusually tailored, his ear preferring the musicality of a sequence’s totality over the whirring and grinding machine that’s been framed right in front of your face. Much like how The Doof Warrior in FURY ROAD would be noiselessly strumming, there are full-contact foregrounded crashes in FURIOSA that are totally silent because the tones of the crashing and clanking are not playing the right notes for the tenor of the scene. If it isn’t the right instrument for the moment, then Miller takes advantage of the artist’s role as God. For us—the already dead—seeking sensation to make us still feel alive, FURIOSA is the type of expiring epic that helps wash away the sorrow. This degree of diligently psychotic craftsmanship deep in the corners of the world’s harshest deserts and harsher green-screen studios to depict a world ravaged by the elite’s rampant waste of resources is a level of hypocrisy that can only elevate the final product of a Hellbent madman like George Miller. Excess in a sandbox of waste-not: Miller’s joie de vivre is one and the same with the psychotic warlords of his mind palace who violently shape the landscape to their own whims. That the international filmgoing crowd couldn’t bother to show up for it after all Miller has done for us is a stain on the history of the medium. [Kevin Cookman]

16. THE BRUTALIST

Director: Brady Corbet

You understand what Brady Corbet’s 2015 debut THE CHILDHOOD OF A LEADER is getting at even before the title card. The rest is just watching a student of Von Trier and the rest of the European nihilists have a wank over the eight movies he’s copied and the two historical texts he’s partially annotated and handed off to a production designer. And you struggle to comprehend what Brady Corbet’s noxious 2018 VOX LUX is getting at through its interminably smug snickering about “the current state of affairs.” When rumblings of THE BRUTALIST—a nearly four-hour descent into 20th century art and commerce produced with the catering budget of a Marvel movie—arose in September out of the Venice International Film Festival premiere, 2024’s most miraculous hype cycle kicked off at mach speed (perhaps out of desperation coming out of a wretched summer movie season, perhaps because there are actually Brady Corbet fans out there), but I remained skeptical until December. How good can a film be by an artist of, at best, wobbly standing who’s spent his entire career bending over backwards to prove he’s made the defining films of his era?

As it turns out, every person has the capacity to improve and no one can ever truly be counted out. Tasking himself with the moral constraints of maneuvering the memory of the Holocaust disallows Corbet from rolling around in the bulk artisanal narcissism of his previous disasters and forces him to lock the fuck in. We all win, and THE BRUTALIST transcends being a monument to itself. There are many movies in THE BRUTALIST, but I adored the one about an anarchist-adjacent Hungarian Jew turning an effigy for his maniacal multi-millionaire WASP benefactor into a Pennsylvanian crematorium. At the core of THE BRUTALIST is a totem of spite—Corbet’s ambitions of sticking it to an industry fueled by fraud-intellectuals-turned-rapist-benefactors recoil in comparison, but it doesn’t not strike a cord, no matter how lesser they are to László Tóth’s completely fictional resistance. THE BRUTALIST imports the significance of meeting the magnitude of yourself, and becoming a fascinating object especially because of the moments you don’t. In scope, technique, and as redemption for his previous defeats, Brady Corbet has at last produced one of the grandest achievements in independent cinema. [Kevin Cookman]

15. HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS

Director: Mike Cheslik

Dearest Merry-Go-Round Magazine reader… You read our weekly Bandcamp Picks of the Week, tap into our artist interviews or reviews of indie arthouse flicks, and share our brutal pans of studio slop… You, more than anyone else, understand that there is no such thing as a meritocracy. Something that is good does not certify that it will be popular or even regarded. Something that is excellent will not attract attention solely because it is excellent. Something that is incredible does not automatically rise to the top of the charts, and something great will often garner a “Who gives a fuck?” You, Merry-Go-Round reader, are well aware that being dope is designed by the media economy to get you nothing. And so it is a modern miracle that HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS emerged from years on the festival circuit to become one of the few genuine cult hits of the last 20 years. Through word of mouth, boutique Blu-Ray releasing, and fervent roadshow screenings, the stupid and stupendous HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS was the myth of meritocracy realized. The clockwork serenity of HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS is some of the most brain-massaging cinema I’ve ever seen, like watching a perfect playthrough of a survival sim by a streamer who’s conveniently finding all the silly, non-game-breaking bugs. And it is goddamn funny to boot.

You’re left wishing the film was double the length so you can spend longer soaking in the zen of Jean Kayak checking in on his rabbit trap, fixing his mega-automated beaver scythe, sneaking up on the wolf den again, back to the fishing rig, past the dam, buying power-ups from the merchant, swapping items with The Indian Fur Trapper, falling in a hole, starting the day over, and resuming a similar cycle over and over again. It’s a film that defies silent cinema foundations and even the tenets of comedic narrative fiction, instead embracing the progression loop of a manic STARDEW VALLEY marathon. Simultaneously, HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS’ process is achingly similar to Kevin Costner’s award-winning DANCES WITH WOLVES, a film whose fleetingly prime moments see Costner run through the home-making procedures of tending to his abandoned fort. However, in the grand scheme of capturing the absurdities and eccentricities of the American frontier—and how nature sublimely and destructively interacts with itself—Mike Cheslik got the Best Picture winner handedly beat. Constructed with consumer-grade equipment, moxie, and a few dozen mascot costumes, HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS is the only film from 2024 that felt like watching something brand new. [Kevin Cookman]

14. I SAW THE TV GLOW

Director: Jane Schoenbrun

Liminal spaces have taken up an inordinate amount of the internet’s collective psyche over the last five years; there are few things people currently find more dread-inducing than the sense that we are stuck in purgatory, in an in-between place waiting for something to happen and fearing that nothing ever will. It makes sense in a decade that started in pandemic isolation, but in a deeper sense we all know we are stuck at a liminal moment of history. There is a real chance that no great catalyst will take us off the trajectory we’re on and that we will all sit in our houses and stare at our screens until climate catastrophe or the fascist boot comes to our front door and takes us for good. A lot of great fiction over the last few years has seized on this feeling of being trapped in the in-between: There’s a reason SEVERANCE is such a direct hit, or that Kyle Edward Ball’s SKINAMARINK pushed audiences’ fears of being trapped and powerless in a house we can’t escape to their farthest point. But perhaps no other artist has captured the terror of being trapped at the threshold quite like Jane Schoenbrun’s masterful I SAW THE TV GLOW. Few films so far this century have captured the terror of knowing that we have to change—that the only way out of the conditions trapping us all is to radically transform ourselves—but that that change so often feels too impossible to contemplate.

Schoenbrun is nonbinary and it’s clear they wanted to tell a story about the terror of admitting that you don’t fit within the confines of the gender binary. It’s extremely moving from this perspective; I have never more viscerally understood what it’s like to come out as trans as a cis person than I did sitting through this film. My dear friend, Annie Howard, wrote this beautiful review of the film if you want to read a trans critic’s perspective. Yet, I think the reason the film resonates is because anyone can relate to the feeling of being a young person and knowing you need to cross a threshold to become the fullest version of yourself, even if that means alienating and leaving behind everyone you grew up around. The sensation that your life can never be bigger than your hometown—never bigger than working minimum wage jobs in the strip malls you grew up around—pervades every corner of modern life. We’re all trapped in liminal spaces, waiting for someone else to open the door for us, and Schoenbrun reminds us that the only person who can is you. [Carter Moon]

13. ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT

Director: Payal Kapadia

Payal Kapadia has been making films for approximately a decade. After studying at the Film and Television Institute of India, her short AFTERNOON CLOUDS (2017) was the only Indian film chosen to play any sidebar of Cannes that year, and her debut feature A NIGHT OF KNOWING NOTHING (2021) later won the Golden Eye award for Best Documentary. The docu-fiction hybrid is a poetic testament to passionate student protesters and their inner emotional lives, quietly subverting the traditionally negative images of student protesters we are used to seeing in the mainstream media (if you haven’t seen the film, it’s on the Criterion Channel, go check it out). 2024 was the year Kapadia truly broke out onto the world stage as an artistic force to be reckoned with. Her city symphony, ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT, became the first Indian film to compete for the Palme d’Or in 30 years. Kapadia took home the Grand Prix for her love letter to the lovelorn women who live and work in Mumbai, becoming the first Indian filmmaker to do so.

The film follows two nurses, Prabha and Anu. Nurse Prabha (Kani Kasruti) is the experienced and uptight one who receives a gift from her estranged husband whom she has not seen in over a year, and is pursued by a doctor that she rejects. Prabha’s roommate, Anu (Divya Prabha), a younger woman, struggles to find a private place where she and her boyfriend Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon) can have sex. Their love is forbidden because he is Muslim and she is not. The lovers tip-toe around the city in search of nooks and crannies for smooching, hoping to avoid judgment from even Prabha. Between shifts, Prabha and Anu also help out a third woman, the cook at the hospital Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam), to relocate back to her village after she is forced to leave her home by a greedy landlord. The subtle solidarity between the three women is authentically touching, especially the final shot of them chatting under the sparkling lights of an outdoor shack. ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT is far more tightly controlled than her previous feature, but it still leaves enough room for the women’s lives to breathe. This might be a touch too rambling for some viewers, but if you don’t mind a bit of aimless wandering around the city, this film is for you. The piano score by the Ethiopian pianist and nun Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou lends the film an intimately romantic layer; if you’re feeling personally or creatively stuck, take a long walk around your neighborhood while listening to this score. You can thank me later. [Katarina Docalovich]

12. QUEER

Director: Luca Guadagnino

William Burroughs’ 1985 novella Queer is irredeemable trash. Written amidst a narcotics-informed delirium, the book indexes Burroughs’ hedonistic stint in Mexico through his fictional stand-in William Lee. In an enclave full of foreign transplants, Lee lives lavishly and lasciviously, all while spewing racist diatribes at his host country. Our dear protagonist—that is, Burroughs—is doltishly unaware that it is precisely the twin forces of dollar hegemony and white supremacy that’ve enabled his expenditure. Burroughs, albeit unwittingly, implicates himself as a foot soldier of American imperialism.

All this considered, I had extremely low expectations going into Luca Guadanigno’s 2024 adaptation of the novel, also titled QUEER. What I saw surprised me; the film gleans the best aspects of Burroughs’ novel, all while maintaining a reflexive, critical gaze towards its inherently problematic narrative. Like Fassbinder’s QUERELLE, Queer unfolds in a city decorated with uncannily perfect storefronts and painterly skies, sexual liberation and an endlessly jubilant vibe (literally every local character wears a mile-wide smile). The aesthetic artificiality here serves as a reminder that Lee’s Mexico is an utter farce: a hyperreal that only exists for detached foreigners with money to spend. Remarkably, Daniel Craig, who has built his career being the guy that straight men are obsessed with, stars as Lee: a fragile, insecure failure of heternormative masculinity. Fancying himself an overlooked dandy, Lee spends his time dallying across town in a white-linen suit, desperately hoping to be seen. During one of these promenades, Lee encounters Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), a young, clean-shaven, all-American gent who easily passes as a Leyendecker creation. This sequence is stunning; scored to Nirvana’s “Come as You Are,” Lee cooly saunters through the block, passing local prostitutes working up their Johns, drunks leaning against brick walls, and an obviously symbolic cockfight. When Lee looks up, he is literally stupified by Allerton’s parallel gaze. The entire film is foreshadowed and signified in this moment of hot desire. We very much get a sense that the seed of a self-annihilating love has been planted—perhaps it’s already bloomed. For the rest of the film, Lee pines over Allerton, trying every tactic to woo the younger boy from awkwardly following him on the street to lashing out in repressed rage: a grown man transformed into a petulant little boy. Allerton, equally as guilty, fuels Lee’s pathetic behaviour with his occasional reciprocations. It’s hard to watch this sadomasochistic ritual. Anyone who’s ever been “down bad”—by which I mean everyone, for no one escapes life without suffering through a debasing love affair—will simultaneously cringe and sympathize with Lee’s pathetic predicament. Guadanigno has brilliantly transformed Burroughs’ reactionary novel from a particular auto-biographical account into a universal work of art. [Vicky Huang]

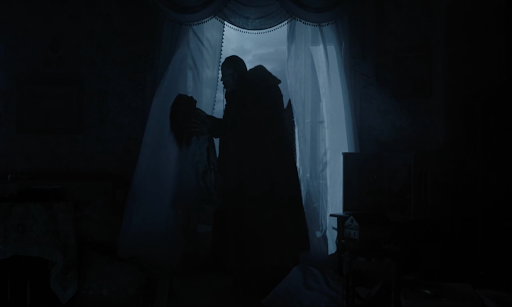

11. NOSFERATU

Director: Robert Eggers

Since the first Trump presidency, there’s been an aggressive reassertion by Neo-Nazis and their collaborators that Western male chauvinism is something to be championed as the historical force that created our modern world. Rober Eggers’ entire career has existed within this political context and can be interpreted as a refutation of this ideology. Over the last decade, THE WITCH has steadily cultivated fantical devotion from people who want to “live deliciously,” rejecting the trappings of puritanical patriarchy and living for the exploration of their own desires. When THE NORTHMAN was initially released, images of rolly-polly white nationalists sieg heiling with popcorn buckets in their laps made their way around social media; they gleefully expected the film to be an affirmation of their Aryan pagan fantasies. In reality, the film is about the dangers of clinging too hard to the legacies of kings and the honor of dead men. Now enter NOSFERATU, a film about the vice grip of patriarchal ownership over married women’s lives in the early 19th century and the contracts that bind them to men.

In our era where bodily autonomy to have an abortion and to choose what hormones go into your body is directly under attack, the film is essential and subversive. Starting his film in total darkness as an isolated young woman named Ellen cries into the void for relief from her psychic torment, only to be answered by a demonic predator who takes possession of her, Eggers makes it very clear that NOSFERATU is about the isolation and exploitation of women. It makes sense that this was the film he wanted to make immediately following THE WITCH, as the thematic throughlines of women in puritanical cultures succumbing to a darkness that threatens the social order could not be clearer. Making Ellen the narrative heart of the story proved to be a powerful deviation from Murnau’s original, the tragedy of her dark pact with a primeval force raising sticky questions of her agency or lack thereof. Ellen is desperate to articulate her dark circumstances to anyone who can listen, but the social mores of the time prevent anyone from being able to see her as anything more than “melancholic.” The film viscerally reminds me of Silvia Federici’s incredible book Caliban and the Witch. That book tells the history of the development of modern patriarchy in Europe through the lens of the enclosure of the commons and the transition to capitalist production. She demonstrates in that book that the femicide of women that took place in the form of witch burnings wasn’t simple Christian superstition run amok, but a disciplining of women who had practiced forms of healing and held privileged positions in society into accepting their place in subordination to men. She demonstrates how violence against women was systematically endorsed as a way to claim their sexual reproduction as the property of men. Ellen desperately wants to fit into the confines of patriarchy; she wants to be a good, normal wife, but she is incapable of it. The struggle between men who want to dominate women and women’s freedom may be an eternal one, but it is one that has always been resisted and fought. Ellen may succumb to her predator, but it becomes an act of revenge, a knowledge that she alone can force his hand and can exploit his hunger to his own demise. [Carter Moon]

10. HARD TRUTHS

Director: Mike Leigh

Mike Leigh has claimed in interviews that HARD TRUTHS wasn’t conceived and developed as a post-COVID character study, but given the societal and behavioral riffs that we continue to see in the years after the epicenter of the pandemic, I do think it’s fair to read the film in that light. Marianne Jean-Baptiste gives a tour de force performance as Pansy, a London housewife whose anxiety, depression, and anger are an unpredictable and combustible timebomb. In true Mike Leigh fashion, these outbursts are met with a range of sympathetic and indifferent reactions from character to character. For her meek son and spiralling husband, they can only quietly lament her toxicity, seeing and trying to accept a clearly changed woman. Her sister Chantelle can simply compassionately grimace and laugh at the woman she’s become. Pansy doesn’t like leaving the house and when she does, we see these uneasy blowups happen to strangers, be it with her doctor’s office or at the grocery store—the world is hard, but for Pansy, it’s harder. Leigh’s lens is, as ever, subjective, a Rorschach test of familial relations that will shift from audience to audience; certainly the COVID reads on this story come from many people (including myself) seeing in Pansy the very obvious before-and-after effects that a rapidly changing and often freefalling world has had on friends, co-workers, and family. But its final summary, coming from Chantelle, is as tender and understanding as you can hope for people stuck in this perpetual state of self pity and grief: “I don’t understand you, but I love you.” May we all have that kind of patience going into the future. [CJ Simonson]

9. EVIL DOES NOT EXIST

Director: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

There are fewer and fewer places and institutions left that haven’t been affected in some way by the ravages of free-market capitalism. The brute logic that there is a market for anything and everything has destroyed everything from healthcare to climate, feeding a gargantuan beast that is always hungry for more. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s EVIL DOES NOT EXIST—his first film since the Academy Award-winning drama DRIVE MY CAR—sees the free market arrive at a small Japanese rural town with potentially disastrous consequences. Hitoshi Omika plays local handyman Takumi, who finds his village of Mizubiki disrupted by a Tokyo-based company that plans on introducing a glamping site near the town. The representatives of the company are entranced by Takumi and plan on using him to ingratiate themselves to the rest of the village, with potentially disastrous consequences. The centerpiece of EVIL DOES NOT EXIST is the town meeting where the company representatives introduce themselves and describe their plans for the glamping site. As the sequence goes on (for nearly 25 minutes), more questions are raised by the townsfolk and it quickly becomes clear that the plans would dramatically pollute the local river that is the village’s lifecenter. Not only that, the representatives themselves have nothing to do with the plan, and are in fact talent outsourced by the glamping company to travel to Mizubiki and give this presentation. The meeting perfectly illustrates the nature of how capitalism in the 21st century works: The glamping site is not meant to be sustainable or long-term, but a quick stream of income that can be disinvested just as quickly as it is created. This point is further brought home by the following scene where the two representatives have a Zoom meeting with the company CEO. He assures these actors that it doesn’t matter how the meeting went because the meeting itself is just part of a bureaucratic checklist that they can now cross off.

Though the prospective glamping site would negatively affect the town and the surrounding environment, who can we blame for it? The two actors traveling to the town are little more than cheap public relations hires who had nothing to do with the plans themselves. Hilariously, one of the representatives, Takahashi, takes a liking to Takumi and even expresses a whimsical interest in moving out to Mizubiki from the stress and costs of city life. For the company CEO, this is likely just one of a series of financial investments; the Zoom call with him takes place in his car, almost like the glamping site and the fate of the town is sandwiched in the break between two more important meetings. Hamaguchi seems to suggest with the title of his film that evil does not exist because we are all just small cogs in a larger machine just doing our jobs in our own isolated sections of a nefarious system. Regardless, the violent disruptions that conclude EVIL DOES NOT EXIST shatter the illusion that anything can be resolved between the interests of the town and the interests of the company. [Ethan Cartwright]

8. SING SING

Director: Greg Kwedar

Prison movies are one of the most difficult genres for me to motivate myself to watch. As Americans, we are inundated with the knowledge that any small slip or demonstration of free will could lead to us winding up in the carceral system, and our films often reinforce this—they’re either slow marches towards death where everybody’s hands are dirty or saccharine inspirational stories about miracle people who rise above it all through sheer determination. I wasn’t sure exactly which to expect from SING SING, and what I got was completely unprecedented. This isn’t a movie about crime, as we are only given hints as to what these men might’ve done to wind up in their situation. And the prison isn’t an omnipresent character—we’re not subjected through the 10-minute-long tour where the guards ramble on about how tight the doors lock and how there is no escape. Instead, it is merely an unfortunate backdrop wherein a group of men are forced to find some semblance of joy within their terrible circumstances. They do so through the very medium we are actively witnessing: acting.

With the exception of Colman Domingo, all of the performers who comprise the members of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program were actually incarcerated themselves. What they bring to the film isn’t just a loose construct of “authenticity,” but full-bodied portrayals of what healing actually looks and feels like. Most of SING SING plays out as a process-driven piece about the rehearsals for the troupe’s upcoming show. Clarence Maclin frets over delivering a monologue. There’s bickering about blocking and costumes. Domingo’s Divine G is both a diva and mentor, herding these guys to express themselves deeper while still wanting all of the best material for himself. It’s only when they step away from the rehearsal space that we again become aware of the hole these men find themselves in, and with each passing second, we pray that their renewed sense of self will find a way out. SING SING is a beacon of light in a decade where we all find ourselves even more likely to be at the mercy of the American justice system. Even if that monolith refuses to forgive these men, SING SING invites us to do so, and to hope for a future where such empathy can become the norm. [Michael Fairbanks]

7. THE BEAST

Director: Bertrand Bonello

In the future, AI has advanced to the point where it has dominion over the Earth. Catastrophic climate change has largely been avoided, but the streets of Paris are grey and empty and the air is toxic enough to require humans to walk around with gas masks. Humans struggling with employment can undergo a procedure that aims to resolve conflicts in the participants’ past lives, dulling their empathy and making them better workers. Lea Seydoux is Gabrielle, unemployable in this future due to her deep well of feeling, who undergoes this procedure to improve her chances of landing work. Gabrielle crosses paths with Louis (George MacKay), who is also considering undergoing the procedure as well. Gabrielle and Louis’s past lives intersect in 1910 Paris and 2014 Los Angeles. In one, they are clandestine, doomed lovers. In the other, he’s an incel stalker she finds herself inexorably (inevitably?) drawn towards. As Gabrielle undergoes the procedure and tries to resolve her past lives, Bonello documents the psychic nexus of desire, repression, and connection with creative liberation. His vision of an impersonal hereafter where emotion has been eradicated is one of the most unsettling and plausible visions of the future I’ve ever seen. Lynchian is a word that gets thrown around fairly liberally when trying to classify outré works of the semi-mainstream, but it applies to THE BEAST. For days after seeing the film, I thought about a scene from early in the second season of TWIN PEAKS in which Major Garland Briggs has been captured and tied up by Windom Earle. “Garland,” Windom sneers, Angelo Badalamenti’s score low and dreadful underneath the scene, “what do you fear most in the world?” Drugged and disoriented, Briggs replies, “The possibility that love is not enough.” This quote rang in my head for days after seeing THE BEAST, an unsettling, dread-soaked sci-fi abstraction of the past, near-present, and future. [Mason Maguire]

6. NO OTHER LAND

Director: Yuval Abraham, Basel Adra, Hmdan Ballal, Rachel Szor

At the time of writing this, a brittle Hamas-Israel ceasefire is making a proposed U.S.-led ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip and hinted annexation of Palestine’s West Bank more likely by the day. While the second Trump presidency is producing novel horrors, these strategies are mere follow-throughs of Joe Biden and Antony Blinken’s pre-established, barbaric war planning; the major difference is that we’re back to a 2016 political era of saying the quietest part proudest. Also at the time of writing this, NO OTHER LAND—almost a full spin around the sun after its buzzing debut at Berlinale—is in its first leg of roadshow screenings at participating American theaters after a year of domestic distributors ducking and weaving it. Janus, NEON, A24, Magnolia Pictures, Kino Lorber, IFC, Bleecker Street… What’s up, gang? You good? At the time of writing this, I’m staring at a photograph of a little girl in Gaza covered in blood from an IDF gunshot wound, tracking tiny crimson footprints. Last October, I saw the video of a Palestinian man getting shot in the gut by an illegal Israeli settler invading Masafer Yatta; he falls to the ground and desperately crawls into digital anonymity, while the terrorist continues pointing his assault rifle at children. A year later, in NO OTHER LAND, I learned the victim’s name.

Zakaria al-Adra. The cousin of Basel Adra, the director and primary subject of the film.

And in that one moment, a dozen threads were suddenly connected, this video out of thousands of a nameless man maimed now given an identity, distinct socio-geographic history, and a full family tree. In the west, the discussion of this conflict is mired down in intellectualization, and, well, discussion. We lionize the noise of our voices, the rhythm of our prose, and the tone with which we deliver carefully crafted talking points so as to not give off the wrong impression. There’s no one to snap us out of this rhetorical masturbation, no one to say, “Fine, you guys can talk, but at least help us move these mattresses out of this bulldozed home.” The directness of what’s been crafted in NO OTHER LAND is incomparable. It’s one thing to read about psycho West Bank settlers, and it’s a full other to be behind the lens of someone who runs up to a village crawling with a hundred of them all setting their sights on you. Your blood will run ice cold. Why has this film risen? Why now? Rumblings from cynical dead-enders that NO OTHER LAND has garnered more steam than other Palestinian cinema thanks to its involvement of Israeli creatives isn’t untrue, but it’s impossible to remove the picture from, well, the big picture. In fact, yes, it does make sense that the polished tone piece about West Bank colonizers was able to achieve its sleek construction due to half of its creative team living as sympathetic occupiers with ready access to hard drives, camera tech, electricity, and the liberty of safety. Consider that even with this pedigree—Hell, even with a motherfucking Oscar nomination under its belt—the film is still blacklisted.The most essential cinema of 2024, NO OTHER LAND is being consciously buried from your consciousness. A revolution has never been televised; we must show one another that it is possible, and that it exists. It’s a tall and scary order, but there is unthinkable power in sharing the filmed image. [Kevin Cookman]

5. A DIFFERENT MAN

Director: Aaron Schimberg

As soon as I saw A DIFFERENT MAN at New Directors/New Films, I instantly knew the darkly funny body horror both checked all my usual boxes and scratched an itch I hadn’t previously realized was there. Over the course of this one film, Aaron Schimberg expands the limits of body horror, plumbs the depths of human dishonesty and desire, and investigates the intersection between class and ability. Even when the plot takes a sharp turn in the third act, Schimberg never loses sight of his central question of what defines us without ever turning that inquiry into a moral lesson. His artistic impulses have led him to subvert stereotypes surrounding disability in his two previous features, GO DOWN DEATH and CHAINED FOR LIFE, and the same is true here. It’s always fun when a conventionally attractive actor takes on the role of the maladjusted social outcast, and Sebastian Stan does excellently here as Edward; Renate Reinsve does great work as the manic pixie playwright, Ingrid, but the element that repeatedly draws me back to A DIFFERENT MAN is Adam Pearson’s effervescent performance as Edward’s foil, the all-too-charming Oswald.

In my favorite cinematic moment of the year, Pearson sparkles on screen as he flawlessly performs a karaoke rendition of Rose Royce’s 1976 soul single “I Wanna Get Next to You” without a hint of irony or insecurity. Everything that Oswald needs to thrive is already inside him despite his disability, and Edward could not possibly seethe any harder with jealousy in that moment. Edward’s false belief that his beautiful face transplant, along with his rapid rise up the class ranking, would fix his entire personality has betrayed him, and Oswald is the singing proof. Stan and Pearson react well off each other throughout the entirety of the film, but this purely visual moment sticks out in my mind. A DIFFERENT MAN is littered with visual moments like this one: moments that evoke hilarity, horror, and sorrow. A poorly timed ice cream truck causes a minor inconvenience, large objects fall from the ceiling, new faces and personalities are revealed. The high frequency of inopportune, unusual, and often unwelcome events fits in seamlessly with the New York City setting. If you must choose only one Sebastian Stan vehicle from 2024 to watch tonight, it should be A DIFFERENT MAN. [Katarina Docalovich]

4. NICKEL BOYS

Director: RaMell Ross

Writing about NICKEL BOYS feels a bit like musing on architecture. Told largely in POV shots from two boys sentenced to reform school in Civil Rights-era Florida, RaMell Ross’s transfixing narrative debut succeeds in encompassing and transmitting lived experience and history by upending the traditional way of seeing in popular cinema and creating a tapestry of sound and moving images that transports you through time and space. The subject matter is heavy, covering one of the darkest events in American history, but it is not a hopeless film. With focus and deep emotional intelligence, you leave the theater feeling shattered but hopeful about the future, endurance, and possibilities of the moving image. NICKEL BOYS is one of the rarest things in popular cinema today: a genuinely radical work. [Mason Maguire]

3. CHALLENGERS

Director: Luca Guadagnino

Art would be nothing if there were no obsessives with unmatched minds for exploiting other men’s primality in pursuit of showing the world some good fucking craft; this is nothing if not a loud and profound directorial signature forehanded directly at your chin in CHALLENGERS, a late-period Amy Pascal production that sees Guadagnino operating at the height of his classical Hollywood ideations at MGM, pumping out a steamy, high class melodrama in 41 days one year after a morose cannibal road trip romance and one year before a star-studded campus #MeToo thriller. The bracing modernity of Guadagnino’s work makes his contemporaries look like yellow bellies: auteurs who’d sooner lay down millions of dollars on period-specific antiques than figure out how to utilize Tinder, in-app banking, and Uniqlo brand deals as ciphers for lust and control. Art’s breakfast regiment—the only time I’ve seen AG1 outside of a YouTuber sponsorship—dishes more insight on character and the human body itself than most other 2024 cinema could drum up. When Kuritzkes’ bromo-erotic banter starts getting too cute, Reznor and Ross’ pulsating beats drown out their dueling tongues and reorient our interests around their sexualized archetypes (the film’s towering centerpiece is a bout of interrupted coitus wherein a fleet of synthesized bass is the only apt accompaniment to Zendaya’s viciousness).

It can feel like kids dressing up like grown-ups, Luca making his boys constantly yield beef on sticks, stubby soda bottles, and sometimes just each other’s respective meat, while an electrifying Zendaya will more readily pass for 18 in another EUPHORIA season than a 30-year-old career-mother. But, when you have the hormonally charged heights of this love triangle play like kabuki theatre, it’s impossible to cling to the reality we often so foolishly grade cinema by. This is reality as it exists in the space between the heart and groin. Guadagnino, like many greats before him, expresses a flagrant disrespect for the sport at the crux of his story. Anecdotally, tennis enthusiasts I’ve reached out to cling to a bewildered hatred of CHALLENGERS (“Why did that hotel bedroom scene turn into an interpretative dance?”), whereas every indoor kid I know is in startling agreement that I’m a Tashi. There is a degree to which this content is beneath Luca, and he expresses it clearly. In reality, his awards campaigning overwhelmingly favored QUEER, the second and more prestige of his fantastic 2024 offerings, but the fervor of what will likely be the most crowd-pleasing piece of his career has already cemented CHALLENGERS as a new classic. The point of consumptive, burning passion is to centralize your entire life by turning everyone and everything into coal until you surround yourself with compatriots who do the very same. You don’t want to talk about tennis? Then what’s the point? If you know, you know. [Kevin Cookman]

2. THE SUBSTANCE

Director: Coralie Fargeat

Imagine a world where all art is fetish content, where the participants and creators are interchangeable commodities foremost designing works to suckle on your pleasure centers as a dulling measure against the fascistic dystopia we’re all scrambling for a shred of self-worth in. Now, stop imagining, because you’re actually living in it: This all sounds pretty fucking dumb when I present our universal cultural ecosystem through a fictional lens, but THE SUBSTANCE is essentially this exercise for a relentless two-hours-and-change. Do you think Frank Henenlotter and Brian Yuzna ever dreamed that they’d influence a disciple—an unassuming La Fémis grad with curly locks and a wry smile—all the way to a Best Picture nomination? Move over PSYCHO and the Universal monsters, because now we’ve got RE-ANIMATOR and FRANKENHOOKER charting the course for prestige cinema’s next chapter. Fargeat crossed the Verhoeven rubicon, making something so brazenly dumb that it sits comfortably amongst the targets it’s sneering at. It’s a mantra that has invited so much scorn from an audience who expects media literacy from everyone but themselves, but it is crucial that the dumbest Cannes screenplay award winner is as stupid as it is.

Coralie exposed the squares; THE SUBSTANCE had Letterboxd scribes walking into a sex club and crying wondering why everyone’s cheating on one another. To find nuance in the industrialized feminine existence is to grant it dignity. Fargeat’s major accomplishment—dipped in Blacked gloss, pumped with enough oiled Caucasian ass to satiate an Encino model house, and communicated with the tactful precision of a drone missile executing a housefly—is a totem of brutish eroticism in an era of nothing but. Scoop away the spewed organs and gore and find a character piece on how intense self-loathing will physically manifest, a striking parable in the wake of global rightwing election victories that are consistently spearheaded by voter blocs of white women advocating against their best interests. I wonder why Elizabeth Sparkle does not get revenge on her tyrannically oafish boss and instead focuses her violence inward, said the blind man. People were hollering and recording the screen at an early autumn afternoon screening of THE SUBSTANCE like they were shooting a Worldstar fight, the room equally brimming with toe-tapping arousal and agape-jawed disbelief. There were better films in 2024—ones with living characters, authentic place, earnest pathos, and sage, world-weary wisdom—but there was no, and perhaps will be no, purer splatter and spectacle. [Kevin Cookman]

1. ANORA

Director: Sean Baker

The first thing you notice is the lights—cheap neon, casting everything in a hazy, electric glow. Then the music, pulsing through the club like a second heartbeat. You can almost smell the air through the screen—perfume, sweat, and the mix of Victoria’s Secret lotion clinging to velvet seats and cash-sticky floors. Men watch with hungry eyes, drinks clutched tightly in their hands. But in every room of the club, Ani (Mikey Madison, in a triumphant performance) moves like she owns the place. She smiles wide, snaps her gum, and makes them believe she’s having the time of her life. Because that’s the job. But the moment she steps outside, the world sees her differently. Sean Baker’s filmography, from TANGERINE to FLORIDA PROJECT, has always captured the beauty and struggle of the working class with such authenticity it feels like you could walk outside and meet his characters in real life. ANORA is no exception. It’s a whirlwind of sex, money, power, and survival—a Cinderella story where the ball is a Vegas nightclub, the prince is a rich Russian heir, and the fairy tale curdles into something brutal before Ani even has a chance to catch her breath. The film follows Ani, a Russian-American stripper in Brooklyn, who stumbles into a relationship with Vanya (Mark Eidelstein), the sweet but immature son of a Russian oligarch. What starts as a transactional fling quickly escalates into a high-speed fantasy—shopping sprees, champagne-fueled nights, and a whirlwind Vegas wedding. The illusion shatters when Vanya’s family gets involved, sending a team of goons to “fix” the situation and erase Ani from their son’s life. What follows is a screwball comedy that spirals into something darker—an aching exploration of class, stigma, and the cruel limits of so-called empowerment.

I find so much beauty in stripper culture—the sisterhood, the colors, the lights, the movement. ANORA captures that world so vividly I could almost hear the clack of high heels against the club floor. But Baker also understands the contradictions at play: A stripper is idolized onstage, then discarded the moment she tries to exist beyond that role. The world loves sex workers in fantasy, but in reality, they’re denied dignity, opportunities, even basic financial security. Most can’t even open a bank account, let alone fly around the world on a private jet and get lost in a mansion too big to feel like home. Wild circumstances, yes, but in many ways, so familiar. I once had a Cinderella story of my own. Coming off the 2008 recession, which hit my family hard, I dated someone rich—like, really, really rich. I moved in with him and suddenly had all the things I thought I wanted: a king-sized bed (with an actual frame, which was rare for a college apartment), a brand-new leather couch, vacations to places I never dreamed of visiting. But loving him and keeping him happy and entertained became a second job. His parents never accepted me. They wanted their son with someone they could show off, someone who understood wealth and knew her place. I sat in rooms filled with luxury and had never felt more alone. The ending of ANORA destroyed me because I’ve been there—that moment when you realize people have always loved the idea of you, but never you. When you see that the power you thought you had was just a smokescreen, a game you’d been playing without knowing the rules. So, when someone finally does break down those walls, that feeling of acceptance, and of inner peace, can sometimes feel like great pain. Ani might come from a different world living through absurd, high-stakes circumstances, but in that final moment, I saw myself in her more than I ever expected. Mikey Madison is electric. From the way she charms with a gum-smacking grin to the gut-wrenching moments where her vulnerability slips through, she makes Ani feel so real it hurts. Watching her, I was reminded of Giulietta Masina in NIGHTS OF CABIRIA—another woman so full of life, longing for something just beyond her reach. We need more movies like ANORA; films that don’t sanitize sex work, that don’t reduce strippers to punchlines or fantasies, that acknowledge the barriers women like Ani face without stripping them of their joy and agency. Baker doesn’t offer easy answers, but he does hold up a mirror to the world and forces us to see what we often try to ignore. And what I saw in ANORA—the fire, the heartbreak, the messy, complicated beauty of it all—was nothing short of unforgettable. [Lauren Chouinard]

Comments