I really wish Michelle McNamara was still alive. A lot of people do, obviously, the loss of her truly exceptional gift for blending investigative reporting with haunting, lucid prose has been felt acutely over the past few weeks as we’ve all watched the excellent HBO documentary series named after her posthumously published true crime book, I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK. On a certain level we all wish, now that Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. has been identified and captured, that she could turn her considerable skills to a different case, but sadly she never will.

These days, though, I find myself also wishing I could read her thoughts on the recent uprisings after the murder of George Floyd in the name of Black Lives Matter, and specifically the demands sweeping the country for the defunding and dismantling of entire police departments. I don’t know that I would agree with all of her opinions, but I do know that a person with her level of empathy, clarity, and knowledge of the inner workings of law enforcement would have a unique perspective.

—

It’s a funny thing, to be a person who considers himself a police and prison abolitionist, and to also be someone who cannot stop myself from consuming true crime stories. Abolition, as I define it, is a process of intentionally diverting resources away from law enforcement and incarceration towards alternative methods of social support until eventually prisons and punishment as we conceive of them now become irrelevant to crime prevention and community safety. It is the belief that if we provided food, shelter, health care, and programs of community support to every person, we could largely eliminate crime from occurring in the first place. It does not mean throwing violent people back on the street with zero accountability or support, and it does not mean simply firing all police and replacing them with nothing, it is a deliberate process of building the world we all deserve so that policing becomes unnecessary for the functioning of society. I take this understanding of abolition from brilliant leaders like Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba. When we live in a country with the highest incarcerated population in the world, where police kill more people than mass shooters in a given year, and where law enforcement agencies take up astronomical portions of multiple cities’ budgets, it is very obvious that we need to radically reimagine the role of policing and incarceration in our society immediately. The unconscionable murder of George Floyd and the subsequent relentless abuse of protesters by law enforcement has galvanized many people to be willing to start considering if not full-on abolition, then at least defunding police.

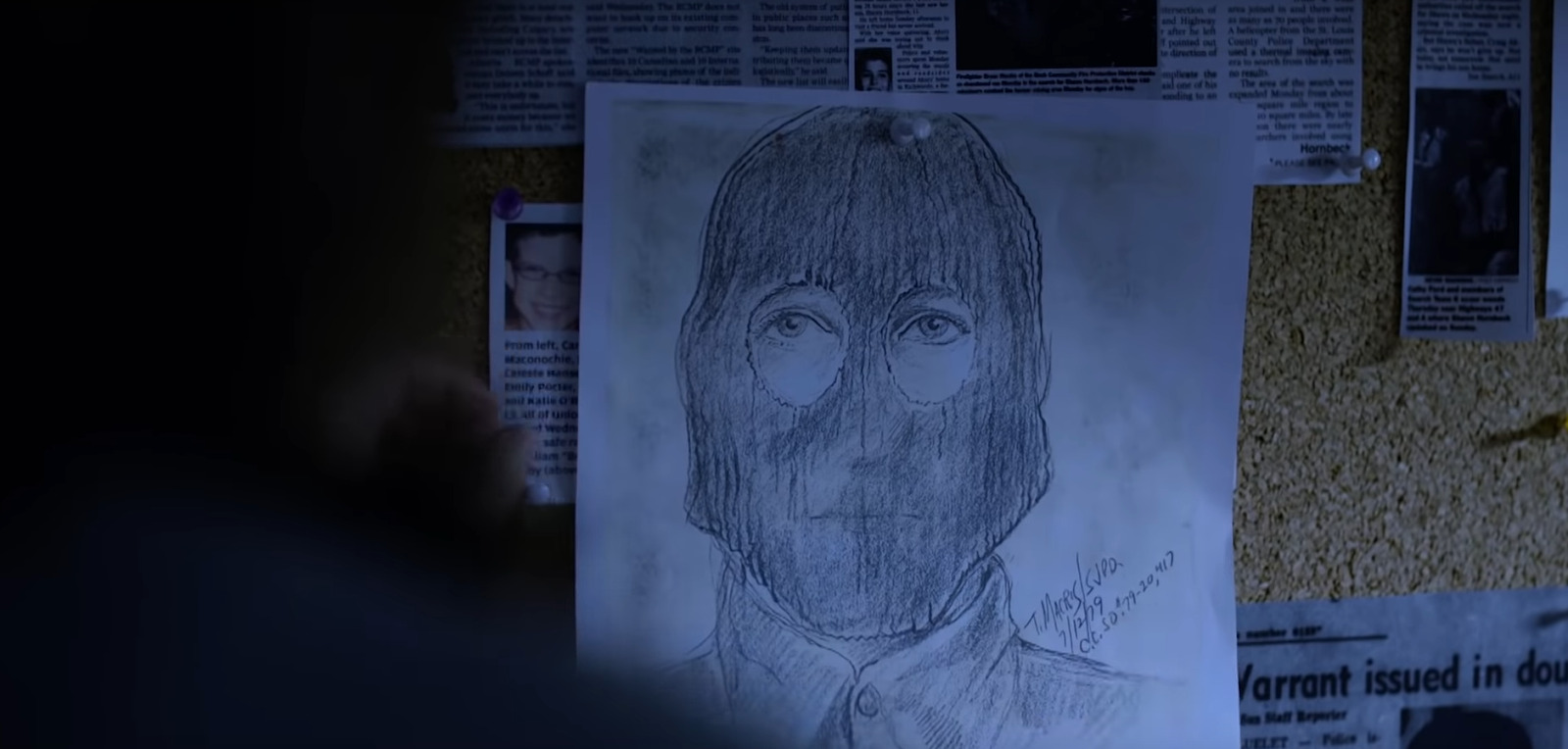

Of course, part of what makes the case of Deangelo so disturbing is that he was himself a cop. As I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK has come up in conversation in the last few weeks, friends have compulsively mentioned: “He was a cop, you know.” It’s such a surreal confluence of events; to be reckoning with the role of policing in society while also reckoning with one of the most horrific stories of serial rape and murder in American history, and knowing that the monster behind them was a boy in blue. Certainly, many people would be quick to jump in here and say “not all cops,” and obviously all police officers are not literally equivalent to the Golden State Killer, but the fact that Deangelo was able to operate as a police officer and remain undetected while committing a series of horrific rapes and home invasions says a lot about the limitations of policing as an institution. When you read and watch I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK, it becomes clear that the detectives investigating the East Area Rapist could never have conceived that he could be one of their own.

I do not think Michelle McNamara remotely considered herself an abolitionist, it is clear when you engage with I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK that she had a lot of respect for detectives, especially the ones who doggedly continued to investigate their cases years after they had gone cold. Yet, when you reach the final episode of the documentary series, it becomes difficult not to feel like so much of how this particular case was handled incorrectly reflects on how we as a society deal with sexual assault and violence against women in general. I could never know how McNamara would respond to recent calls to defund the police, but I do think she would have quite a bit to say about how we could reimagine our approach to sexual violence to better care for survivors. What makes I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK a remarkable advancement in the genre of true crime is how effectively McNamara centers the experience of the victims in her writing. True crime is often accused of making macabre entertainment out of real human suffering (and sometimes that’s certainly true), but it is impossible to deny that both the book and the documentary series emphatically emphasize the experiences of the survivors of Deangelo. Many of the victims interviewed in the series were left to reckon with their trauma entirely on their own, with little to no social support from society as a whole. Decades after many of them were victimized by Deangelo, they finally began to connect to each other thanks to McNamara’s research. It is difficult to watch these survivors have a cathartic meeting at the end of the series, knowing they have been isolated in their trauma for decades. It’s hard not to feel like part of the injustice done to these survivors was the fact that we left them to process their pain privately rather than collectively.

Like any exceptionally well presented narrative, I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK challenges us to ask many questions about how our world could be better. What would a world where investigators of sexual assault were focused on the well-being of victims look like? How would sexual assault cases be solved if the people conducting the investigations were people like McNamara, people with firsthand experience of trauma who had never been trained in the military style of a city beat cop? How can we reorganize society so as to not further produce Joseph James Deangelos? I don’t have full answers to these questions, but I’ve found over the years that discussions with people who are willing to engage with such questions in good faith leads to fruitful conversations, and can directly lead to meaningful changes in policy. Last year, I was part of a months-long campaign to convince voters to support the Reform LA Jails ballot initiative here in Los Angeles, an attempt to scale back Los Angeles’ staggering jail population through community investments and greater public oversight of the LA County Sheriff’s Department. I had lengthy, difficult conversations with people who had never even considered that we could do something with people who break the law other than throw them in a cell. I didn’t always fully convince people to change their minds about incarceration, but I often at least got them to concede that we need to broaden our approach to public safety beyond prison walls.

—

The last episode of I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK gives one of the most succinct explanations for the popularity of true crime that I’ve ever heard. People prefer to consider the worst possible thing that could ever happen to them, such as the Golden State Killer stalking them and entering their home to murder them, because it beats just stewing in vague anxiety with no focus or direction. True crime at its best is a form of exposure therapy, plunging us into the specificity of the absolute worst case scenarios so that the banality of our everyday lives can become a relief in comparison. I got interested in true crime as I was recovering from a severe episode of depression; escaping into the dark reality of serial killers was a great way to step outside of the darkness swirling around my own head. For many, the Golden State Killer is the manifestation of their biggest fears, vividly imagining the experience of his victims is a way to confront that fear. By piercing through the darkness, there is light.

Of course, most of us, statistically primarily women, are far more likely to be raped, assaulted, or murdered by someone we know, especially an intimate partner. The strange thing about violence in American society is that we so often fixate on either chaotic random acts of violence or “justifiable” violence done by the state or for revenge. Our media rarely stops to consider what we need to change to stop the much more common forms of domestic violence that ripple through this culture. If, for instance, someone had confronted DeAngelo when he attempted to attack his fiance Bonnie for breaking off their engagement and he was held accountable not just to Bonnie, but to a wider community of family, friends, and neighbors that had zero tolerance for his behavior, could we perhaps have prevented the worst of his violence? If he had gone to therapy, and particularly group therapy with other men, to process the trauma that was inflicted on him as a child, could the worst of his crimes have been avoided? It’s impossible to know for certain, but what is clear is that our current approach to law and order does not deter the Joseph James Deangelos of the world from existing.

Michelle McNamara was focused on uncovering the identity of the Golden State Killer because she believed that revealing his identity would strip him of so much of the power that he held not over his victims, but over the entire communities that had been terrorized by him. She was of course correct, seeing DeAngelo as a sickly elderly man in shackles instantly strips him of his identity as a faceless monster. But there is a different type of uneasiness that comes from knowing that he was just a man, a man who was a father, a man who raised a niece as if she were his own daughter, after she was attacked in almost the exact same way he attacked his own victims. Serial killers, and all perpetrators of violence, are not somehow separate from the rest of us, they are us, they make up a society just as much as the people who never intentionally cause harm. Monsters are never lurking in the sewers, they are our uncles and baseball coaches and elected officials. As much as American culture attempts to create a sense that once someone chooses to cross over into the threshold of “criminal” they effectively sign away their rights to participate in society, we never can fully, cleanly separate those who do harm from those who do not.

The point of telling stories, in any form, is to understand the world as it is, and to then imagine how it could be. True crime like I’LL BE GONE forces us to see a little more clearly, to understand the undue suffering of others, and to confront the wanton, inexplicable violence that lurks in the hearts of some men. But after we watch it, we the audience are left to imagine how future suffering might be reduced. It is impossible to fully know how to prevent future Joseph James DeAngelos from being made, but we can certainly do better in how we treat victims of sexual violence, and center the healing from trauma in our social processes of repairing harm. We all deserve justice, we all deserve to live in a world where we don’t fear our neighbors, but the world where that is possible doesn’t come from our current systems. We can have people like Michelle McNamara tracking down those who do extreme harm and elude any accountability for their actions without relying on our draconian over-crowded prison system and murderous law enforcement. A better world is possible, we just have to find the strength to step into the light.

Comments