Recent COVID-affected VOD releases, TESLA and SHE DIES TOMORROW, are daring & noble efforts, but ultimately fumble the bag in moments when it matters most.

TESLA

Director: Michael Almereyda

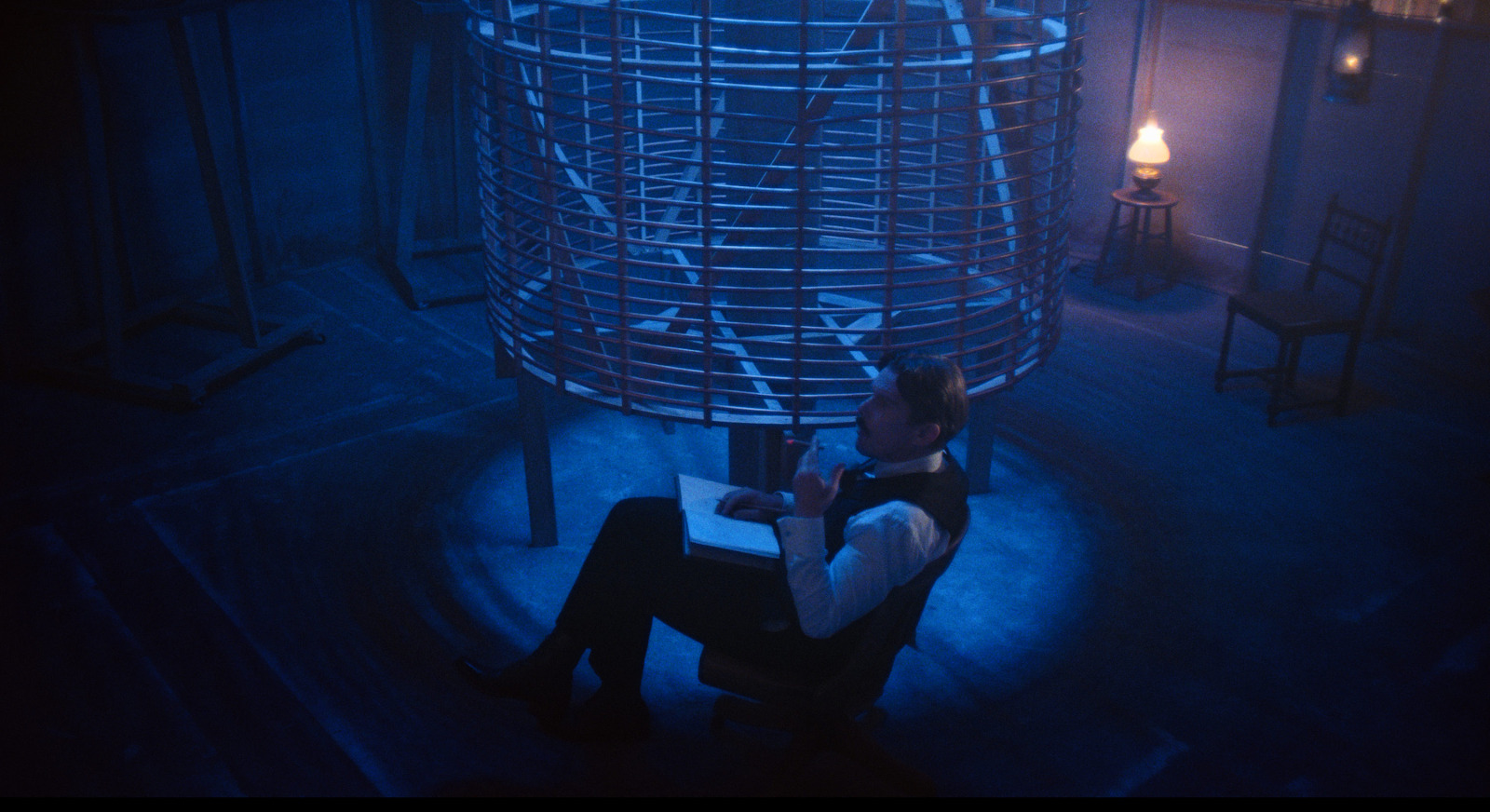

One of my favorite, ultra-specific film sub-categories is “creatively liberal historical dramas designed to get lazy students an F on their term paper.” Michael Almereyda’s TESLA, a word-of-mouth B-side from Sundance, is a conceptually refreshing pseudo-tone poem on the revitalization of 20th century industry, but a far cry from the boldness of Alex Cox’s WALKER, a fellow anachronistic chronicle of American imperialism that, while plagued by a similarly eye-rolling glibness, at least stuck by the immense courage of its vicious convictions. TESLA feels like it wants to be over by minute three. It only takes a small bit for our narrator to yank us out of the bizarre proceedings and literally pull out a MacBook to Google the inventor. Though smugly presenting its own immersion-shattering exposure of artifice as an extension of petty squabbles established between titans of power (Tesla and Thomas Edison had a feud as deep the infinite data well itself—the latter has twice as many online hits than the former), it’s a tad too confident for its own good. You can’t just swing your dick around like this and then have 70% of your movie feel like the droll biopic you’re hoping to skewer, where the extent of its research does indeed feel restricted to just Googling “Nikola Tesla.” I’d much rather revisit the Claudette Colvin segment of DRUNK HISTORY (an actual reference point for Almereyda), a humorous and genuinely educational six-minute production with a respect for bold creativity and, frankly, your time. TESLA’s shining moments are short-lived. Initially playing as an absurdist comedy-of-egos between Ethan Hawke’s accent-fluctuating Nikola Tesla and Kyle MacLachlan’s Thomas Edison, their dueling, scenery-chewing timbres are on the brink of caving in the surrounding walls: A(rrogant)SMR showcasing the inane showboating of middle-aged men and the barely quarter-aged women they dedicate themselves to. The experimental flourishes, like an aggressive deep-blue strobe show of the Tesla coils’ first test, are incredibly welcome amongst the shockingly dense array of sit-down meetings and lectures.

The finale, a mumbled break into pop power ballad, is the perfect recipe of direct messaging and psychology via practice; Almereyda may have been prepping this script since the ‘80s, but it isn’t until Hawke meekly belts into a karaoke microphone that I fully felt the mass of the self-imposed existential weight on his back. For a film that gives off the impression of looseness, its shoulders are awfully taut from attempting to cover every conceivable angle of the Tesla tale, its approach to the subject matter akin to a cat rabidly clawing at a scratching post until it’s nothing but a heap of scattered shavings. That the singing trudges forward into the realistic drudgeries of a semi-surreal recollection of a life just feels pointless—there’s no shortage of biographical reporting on Nikola Tesla, it’s all a matter of minimal photographic evidence, a matter the film itself brings up, so for TESLA to still feel so aesthetically indebted to fact is a waste of the base premise so obnoxiously set forward. Anachronisms charge in like sudden urges to stop cold in your tracks in Midtown to ponder the circuitry of an LED billboard. Nikola and Westinghouse exit an empty banquet hall that’s being turned over by a janitorial staff sweeping with vacuum cleaners. Their initial meeting at a bar is underscored by jackhammers and sirens outside. Nikola Tesla worked in the shadow of his late brother’s potential—the future endears and intrigues as much as it taunts. You can sense why TESLA was gnawing to be made. I’m ultimately glad it was, but will never not be frustrated with the constraints it sets on itself. MacLachlan’s cheeky reading of “Got a light?” only sparked my urge to turn off the film and opt for an annual rewatch of TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN instead, my preferred history-twisting, pulp-Creationist account of 20th-century morality. [Kevin Cookman]

SHE DIES TOMORROW

Director: Amy Seimetz

Amy Seimetz sits in a coolly polymathic space in the middle of American movies. In addition to her acting and producing careers, Seimetz’s directing has helped import a digital filmmaking with unusually warm and layered visual tones into television. Her second feature, SHE DIES TOMORROW, represents a return to features after seven years. In the time since, Seimetz’s direction for Starz’s THE GIRLFRIEND EXPERIENCE located RED DESERT in the late 2010s—presenting a very specific kind of conference room gurgle with a very specific kind of transactional dread. Seimetz continued onto ATLANTA, her strongest episode, “Champagne Papi”, serving as something of a dry-run for SHE DIES TOMORROW, with an arch-comic structure distilling a lightly panicked party with little, acid Buñuel droplets. Characters run around Drake’s mansion to no avail asking one another: Where’s Drake?

I mention Seimetz’s television work so centrally because SHE DIES TOMORROW carries that sort of sketch-like structure to it. There is a female lead by the name of Amy (Kate Lyn Sheil) who has recently purchased a house and is clearly a little out of it, mentally. Amy begins to articulate her certainty to the people around her that she is going to die the next day. Her friends lightly brush off the predictions, continue about their day, and then relate to their friends their certainty of their death the next day. Flashbacks and hallucinations begin to assail Amy; then, they begin to assail everyone else. The movie’s rhythm is to trick you into thinking you are watching something much smaller and more conservative than you are.

Seimetz is playing with how tiny this movie is in many ways. SHE DIES TOMORROW is building towards its own vision of mass, collectivized anxiety—the freakout headspace of MIDSOMMAR, with even harsher, more experimental effects—while frequently misdirecting us. Seimetz will build dramatic cuts to a simple bong hit, or stick the audience with a 30-second beat where Amy will aimlessly scroll through her laptop. You want the shit to speed up and then Seimetz bombs you with an avant-garde Technicolor freakout and then you realize why it was slow. Seimetz is a witty editor in smashing together her more mumblecore origins with a sensibility of the cosmic. SHE DIES TOMORROW imports ATLANTA’s springboard momentum: that stoner-y sort of “snapping to” pace, the up-and-down rhythms in the editing. Unfortunately, the movie is also part of a particular strain of independent cinema where no one talks like a human being. Individual identities are blurred in service of larger thematic schematics, like elements in a chord that’re just too big for “normal people” to understand. The people do not need to talk like people because the people are concerned with death and anxiety. It’s a puzzle movie that is both extremely deterministic in its metaphor and its values, while also very fuzzy in how its direction is intended to affect you. Its ambiguity walks a fine line with sketchiness; the gonzo confidence of Seimetz’s approach here is not enough to lull you out of the sense of the schematic. You are watching a movie about death and anxiety that arrives at its points by people discussing death and anxiety. I am now put in the position of writing about an indie movie that I feel I have seen before—thereby, writing a review you have read before. Bollocks. Where’s Drake? [Ryan Michaels]

Comments