Thanks for clicking into our end of the year coverage! Merry-Go-Round Magazine is an independent culture site funded by people like you! If you’re enjoying our End of 2023 Coverage, consider becoming a member of our Patreon, or even donating to our operation here!

Pardon our tardiness, but blame the cretins who scheduled the 2023 holiday release calendar: after a tumultuous series of labor strikes, studios dumped their product in a two-month burst that not only oversaturated the marketplace, but has left 2024 barren! When a star-studded Enzo Ferrari biopic directed by Michael Mann is getting bumped out of major screens after its Christmas week release, you done burnt the roast. As such, we wanted to take the extra time to catch up before assembling the best of the best, so that you can get a definitive list of the goods. A broadly satisfying consensus year where most ended up liking the same films as one another, 2023 marked the brightest spark yet of cinema’s return to the monoculture, but don’t worry, the weirdos at Merry-Go-Round found some oddball shit for you, too.

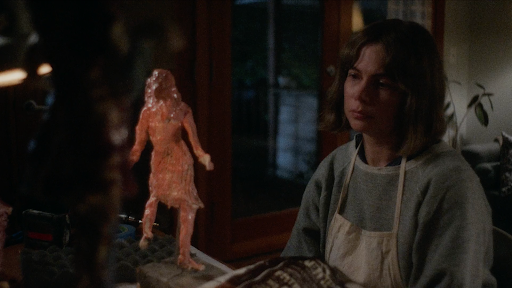

23. SHOWING UP

Director: Kelly Reichardt

I’m not sure I would have responded so intensely to Kelly Reichart’s SHOWING UP if I hadn’t spent the last year watching tech bros and hedge fund managers and brutish philistines degrade the sanctity—neigh the concept—of art. Every day it’s a new horror; using AI to “complete” Keith Haring’s “Untitled Painting,” degrading the artform of jazz, debating the necessity of sex scenes in film—the list goes on, each and every argument stemming from a place of uncontrollable hatred for creativity, a binary view of good and bad, and a hackneyed, misunderstood worldview shared by the dumbest people throughout history.

I fear these people are winning. And I hope they never see heaven.

I watch SHOWING UP and I’m reminded that the process of making art is hard. The process of understanding art is hard. You have to put everything you have into it. Reichart’s latest is a slow rumination on the frustrating, but healing, nature of putting in the work because you have nothing else to make you whole; we’re meant to watch John Magaro’s character Sean dig a pit in his backyard as he attempts to build it into some grander self-fulfilling meaning and believe for a moment that he is, perhaps, losing it. But I see that giant hole and know both it and the film itself would be misunderstood by the same mouthbreathers that get caught posting Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain on Twitter as some form of “Gotcha!” He digs because he has to, and a growing sentiment of anti-intellectualism is trying to undermine and dismiss that. Both I and SHOWING UP say fuck ‘em. [CJ Simonson]

22. AFIRE

Director: Christian Petzold

Something is off from the first minutes of AFIRE. The car breaks down several kilometers away from the beach cottage where friends Leon and Felix plan to spend a week alone. When they make it to the house, they discover another person—Nadja—also staying there and spending her nights with Devid, a local lifeguard. And there are daily warnings of a forest fire approaching. At first blush, German director Christian Petzold’s latest movie is a dry, biting comedy with a setup clearly reminiscent of Eric Rohmer: young, attractive middle-class Europeans on vacation whose relationships with each other are constantly in flux. At the center is Schubert’s Leon, a self-obsessed writer who just wants to use the time away to clear his head and finish his latest novel (titled so hilariously that it’d be a shame to reveal the punchline here). Pretentious and deeply insecure, he frustrates himself over Felix, Nadja, and Devid’s fledgling friendships and romances with each other. Schubert’s performance is one of the year’s most compelling, especially considering how well he balances his character’s obvious unlikability with just enough small gestures to make Leon somewhat sympathetic in his self-made isolation.

Like Rohmer or Hong Sang-soo, Petzold effectively skewers his protagonist as both a person and a creative; his inability to escape himself and properly interact with the people around him severely limit whatever writing talent he has. The tonal shift the film undergoes in its last half-hour is purposefully jarring, as the fires finally reach the spot where Leon and company are vacationing. After Leon spends so much of the movie trying to separate himself from the real world, the real world blazes through with a vengeance. And so Leon does what any artist confronted with trauma and pain does: He turns those experiences into his next project. After all that’s happened in the last four years, Petzold may be doing something similar. [Ethan Cartwright]

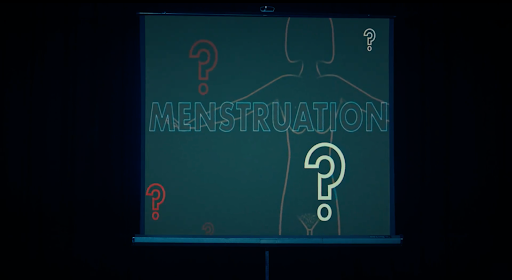

21. ARE YOU THERE GOD? IT’S ME, MARGARET

Director: Kelly Fremon Craig

I hope it doesn’t come off as patronizing to say that 2023 was a breakout year for women in cinema. Any pre-release detractors skeptical of BARBIE’s success were promptly shut up when that movie stomped the box office and remained in the top 10 for 10 weeks. A bona fide non-superhero, non-sequel hit raking in a billion dollars worldwide signals something greater than just a crossover hit: It could very well be a generation-defining film. Any conversation around KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON may have started with placing the film in the late-career context of its auteur director yet invariably circled back to Lily Gladstone’s towering central performance. As of this writing, she seems poised to be the first Native American actor to win the Oscar. Justine Triet’s ANATOMY OF A FALL, a searing French courtroom drama that excavates a woman’s troubled marriage to her husband, was the year’s arthouse sensation and three of the year’s word-of-mouth breakouts—Emma Seligman’s BOTTOMS, Emerald Fennell’s SALTBURN, and Yorgos Lanthimos’ POOR THINGS—seemed to scratch an itch for unashamed vulgarity, with each capturing late-millennial/Gen-Z imaginations and TikTok “For You” pages.

All of the above films have made it on to Merry-Go-Round’s list this year. And of the above films, the one that stood head-and-shoulders above the rest was Kelly Fremon Craig’s tender and mature adaptation of Judy Blume’s oft-banned 1970 middle-grade novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Why is that? And why did Kevin Cookman assign me—a cisman with no familiarity to the source material—the duty of summing up this film’s power? The film left little cultural impression relative to the films I mentioned above. In the wake of Roe v. Wade’s overturning (the novel was published three years before that landmark Supreme Court case), a film about an adolescent girl’s crisis of faith coupled with her anxiety towards hitting biologically determined checkpoints and developing her first crush may come off as a small-c conservative depiction of womanhood. Some may want the film to enter the 21st Century and be more openly political, more openly of our time. And yet, Craig’s decision to keep the film set around the year it was published removes any distractions from the film’s laser-deft and delicate approach to the most important year of Margaret Simon’s life (so far). Her mother (a luminous Rachel McAdams) and grandmother (a warm and lovely Kathy Bates) are themselves struggling with transitions of life and defining their womanhood as well. The film approaches its audience with open arms, the cinematic equivalent of a big hug from your grandmother. Abby Ryder Forston, Rachel McAdams, and Kathy Bates (with an assist from Benny Safdie) were maybe the most believable depiction of a healthy and supportive family unit I’ve seen in years. It’s rare to see a suburban family of relative privilege depicted without an ounce of cynicism. No matter who we are, the one constant in our life is change, and we are defined by how we respond to the challenges of our lives. Them’s the bricks for anyone, kid. That the avatar for this truth in this year’s cinema was a tween girl going through puberty in 1970s Ohio was as miraculous as anything else. Watch it with your mom! [Mason Maguire]

20. LA CHIMERA

Director: Alice Rohrwacher

In 1966, Susan Sontag wrote that “the project of interpretation is largely reactionary, stifling… to interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—in order to set up a shadow world of ‘meanings.’” With LA CHIMERA, Rohrwacher resists the idea of cinema as excavation, ironic considering both Arthur’s illicit tomb raider occupation and the multilayered nature of the story. The ancient tombs are not meant for human excavation, and neither is the film. Yes, there’s the surface-level adventure story about grave robbers being cheated by a greedy art dealer, and the deeper story of Arthur’s search for his long lost love, but if you go digging around for hidden meanings, then LA CHIMERA’s spiritual magic will be lost on you. Instead, let Rohrwacher’s magic wash over you, as the ocean waves wash over the sand. Rohrwacher’s cinema is all about feeling in defiance of intellect, about having faith in the things you cannot see, and that’s what makes it so special. A lot of films that came out this year were fun to dissect (did Sandra Hüller’s ANATOMY OF A FALL character push her husband to his death? Is MAY DECEMBER a camp comedy or a stark melodrama?), but LA CHIMERA stands out as an example of a film that can stand on its own two feet, without any need for “discourse.” [Katarina Docalovich]

Read Katarina’s full review here!

19. PASSAGES

Director: Ira Sachs

There’s a peculiar wonder with which Tomas tells his husband, Martin, he’s slept with a woman. He delivers this news not as a shameful admission, an ownership of a moment of lapsed judgment—but as the sort of “Gee whiz!” discovery usually reserved for a dog bringing you some poor, ill-fated animal’s carcass as an offering. He wants Martin to be proud of him. He wants him to pat him on the back for his adventurous spirit and newfound bisexuality. When he tells him this, amidst a marriage where the mention of sex at all feels like a small miracle, it is as if to say: “I figured out how to fix us.” He’s so convincing that for a moment you wonder why Martin doesn’t take the news better. There was a NEW YORKER op-ed around Christmas on the sudden cultural prevalence (and subsequent bastardization) of non-monogamy. If 2022 was defined heavily by “eat the rich” stories (may we finally be free), 2023 often found its muse in the singular thrills of polyamory—RIVERDALE ended in a polycule, dammit! Amidst a sea of throuples, Jada Pinkett Smith memoir quotes, and Hinge profiles of people with preexisting primary partners, PASSAGES could have easily been nothing more than its least charitable reading—the M/M/F throuple movie. The MPA certainly thought of it as such, infamously slapping the thing with an NC-17 rating for daring to show that gay guys can, in fact, do missionary. (I thought this was common knowledge but, in an exceedingly rare moment, was wrong.)

And the sex is glorious! Let’s be clear: Nowhere else in the year’s film landscape will you find such sensual, authentic lovemaking, in no small part aided by the fact that the people doing the deed are Franz Rogowski, Ben Whishaw, and Adèle Exarchopoulous. Glorious too is Rogowski’s much-discussed wardrobe. More than the movie where evil bisexual Franz Rogowski wreaks havoc in fabulous clothes, though (although that would probably still be a film I’d advocate to include on this list), PASSAGES is a far thornier character study on one of the most unchecked narcissists ever committed to celluloid. Not that the evil bisexual label isn’t accurate for Tomas, per se—both shoes fit, and they’re designer—it’s just not the whole story. Really, it lets him off the hook too easily. It lets us off the hook too easily, even. Rogowski’s Tomas is a harbinger of doom and chaos but, crucially, not of malintent. So when he ‘look, ma no hands’-s his way through admitting his affair, it only works because he’s genuinely convinced himself of his altruism. It’d be easier to take if he was just a conniving little queen, but the character Sachs and Rogowski present us with is something far messier, nuanced, and dangerous than a cursory glance at the film’s general shape would suggest. Perhaps the closest analog we have for conceiving Tomas in the real world is the archetypal demon twink—the insidious, self-important, shit-stirring, queeny bottoms that keep West Hollywood’s bars alive and well. So, in perhaps Sachs’ single most inspired decision among a film littered with them, when Tomas and Martin do finally have sex (pictured, archived in the deep recesses of my subconscious) you can guess who ends up on his back with his legs up. If you take one thing from PASSAGES, let it be this: Never trust a narcissist and NEVER trust a bottom. And if you come across a narcissistic bottom (and God help you if he’s wearing mesh) run harder, faster, and further than you’ve ever run before. Your future self will thank you. [Taylor Lomax]

18. SKINAMARINK

Director: Kyle Edward Ball

2023 was a less-than-robust year for horror at the multiplex, and, upon reflection, the standard was set impossibly high in January by—incredibly—a micro-budget feature shot in the director’s childhood home. It’s a film actually plucked from my nightmares—anything else I saw was doomed to pale in comparison. Kyle Edward Ball’s SKINAMARINK is about two children who wake up in the middle of the night to find themselves home alone and their doors and windows missing. Endless dark creeps ever closer. Familiar objects take on a sinister glow. Toys move on their own, seemingly moved by the darkness itself. Ball keeps his camera away from the children’s faces (except in one pivotally cruel and frightening moment) and focuses his lens on the steadily encroaching dark itself. Set in 1995, SKINAMARINK scratches and pops like a forgotten VHS tape, this static menace bringing to mind a sort of creepypasta HOTEL MONTEREY. His images never afford you the comfort of clarity; when you do recognize something stable—such as the post of a stair rail or a closet door—it’s filmed from a low angle, as a child would see it in the dark, making them tower over the viewer, imprisoning them in this nightmare. The digital grain draws monsters in the dark where there might not be any, and the sound is distorted to the point that even subtitles cannot save you. I ascribe to the common reading that this film is ultimately about child abuse told from inside the perspective of the child’s nightmares. You feel it. I was rattled for days after. The next Fisher-Price play phone I see is going right into the furnace. SKINAMARINK was one of the most visceral experiences I had at the movies last year. When that jumpscare hit (if you’ve seen it, you know) a guttural noise escaped from some place deep inside myself. For the last half-hour to 45 minutes of the film I had to look around the theater to make sure that I was still somewhere solid, somewhere familiar. It was as if I was witnessing my own nightmares projected back at me, 30-feet-tall in a dark, echoing chasm. [Mason Maguire]

17. THE HOLDOVERS

Director: Alexander Payne

As a cinema-going public, I think we can all agree that we were overdue for a fun Paul Giamatti vehicle that could make us laugh [crowd cheers]… but we didn’t realize we needed one that could make us feel, too [crowd “awww”s]. Looking back on THE HOLDOVERS, I place far less weight on the film’s syrupy coziness and dedication to period accuracy than when I originally saw the film at TIFF (shameless plug), instead finding myself drawn toward more minute character details that I maybe didn’t pay enough attention to on the first watch. One detail that sticks out is the casual reveal that Paul Giamatti’s sweaty, grouchy professor, Paul Hunham, and Dominic Sessa’s bad boy, Angus Tully, are both prescribed Lithium for depression. This is the moment that ties together the central thesis of THE HOLDOVERS, while setting it apart from director Alexander Payne’s pre-NEBRASKA filmography: that we’re more alike than we are different. Across generations, what ties Americans together if not our antidepressants and drinking habits? These are the symptoms, not the cause. Payne diagnoses the root of American spiritual rot as a lack of oxygen from the unforgiving boot of capital trampling our necks: Paul bootstrapped his way up to his tenure at Barton, only to be slighted by wealthier peers, and even students, at every turn. His love for life has been whittled down. Angus’ mom is so caught up with the trappings of her new, rich life that she strands her son at Christmas. The Barton school’s head cook Mary Lamb (the excellent Da’Vine Joy Randolph) is on the bottom of the economic heap, as she quite literally serves Paul and Angus; her only son also died as a cog in the Vietnam machine in his pursuit of a better life.

The lines between “critic” and “fan” blurred even further in 2023, but wherever you may fall on that spectrum, this is one film that most people seemed to be able to agree on: Payne’s latest became more than a simple rebound as it cracked the Letterboxd Top 250, as well as a number of critics’ lists. What is it about THE HOLDOVERS that made the film so immensely popular with both critics and mass audiences? It could be the lack of many other compelling, mid-budget dramedies as the budgets of American films skyrocket higher into the stratosphere. It could be how David Hemingson’s sharp screenplay reveals its mechanics only when he chooses. It could be one of or all of the three dynamic lead performances from Giamatti, Sessa, and Randolph. These are all valid reasons, but I surmise the source of THE HOLDOVERS’ popularity is its well of hard-earned solidarity between three misfits who come together despite their different circumstances. [Katarina Docalovich]

16. THE KILLER

Director: David Fincher

Temptations to subsume ourselves in automation will never cease, and might only appear more attractive to generations raised with it as their rock; a bright-eyed 20-year-old will coo with a straight face that they love their TikTok algorithm like it’s a caged chinchilla. I’m the weird guy for groveling about the state of things. We slavishly categorize, we depend on mechanical curation, we panically yearn for the return of a binary, and some of us can’t even appreciate art without rationalizing its role in our productivity as “a focus tool.” If the day came when I felt a natural emotion, I’d get such a shock I’d probably lie in the middle of the street and die. In this rush, there’s been a consensus to sum up David Fincher’s THE KILLER as a fetishistic self-portrait of the mythically megalomaniacal idea of “David Fincher,” but this pat read conveniently skirts the surface of a seedier achievement: Unbridledly misanthropic and more potent than THE ZONE OF INTEREST, Fincher’s crafted a procedural thriller in the open air prison of modern urbanism about our day-to-day participation in a systemic web of death. Fassbender’s dopey assassin is drunk on hustlecore Kool-Aid, referring to the non-efficiencies in his life as “redundancies” as he lines up a soon-to-be bungled shot in an abandoned WeWork. Learn to code, become a psychopathic mass murderer, or haul dumpsters for eight dollars an hour: these are your three choices in a 24/7 corporatized NATO collective, and as unhappy as we are with it, a population of hucksters has spent more effort constructing cottage industries on how to best get 10 grams of protein for one euro instead of burning these systems to the ground. You are but one of the many. There may be sobering moments of come-to, but you are serving a 1.8 to 4.2 death to life ratio: in the grand scheme of violence, you aren’t making a dent in those numbers. So, keep grinding.

The same way you caught up with VANDERPUMP RULES to eat your coworker’s pussy, The Killer has spent his Saturday afternoons watching STORAGE WARS marathons to refrain from eating human flesh. It seems to have worked, as evidenced when he spares the final target because all he did was check a box the same way The Killer checks off “require signature” on a FedEx delivery sheet. Two fellow, serial customers caught in the same act. When he returns home to an idyllic Santo Domingo estate, Fassbender’s eye twitches before a rapid cut-to-black and yet another Morrissey needle drop soothes him into a moral slumber. There’s a chilliness that obviously elicits Jean-Pierre Melville, but there’s also a churlish ornateness to its construction of a socially shattered future that will bring to mind Tati’s PLAYTIME, but the true French analogue to one of the most American films of 2023 is Demy’s MODEL SHOP: hot man silently drives rental cars through foreign streets in a post-revolutionary, transitional wake for not just the medium, but culture as a whole. That it’s a Netflix exclusive is not just a cheeky punchline, it’s central to THE KILLER’s design ethos. It’s the end of the road, and we’re going nowhere fast. [Kevin Cookman]

15. BEAU IS AFRAID

Director: Ari Aster

A singular exploration of anxiety, grief, and guilt: a Russian doll of neuroses? The Odyssey by way of Freud, Kafka, and your least favorite Fox News Uncle? A “men will literally make a three-hour-long movie about mommy issues instead of going to therapy” joke? Fucked up might do the trick, actually. One thing’s for sure: Anyone who utters the words “fever dream” without first standing before Ari Aster’s funhouse mirror, BEAU IS AFRAID, can chug paint. Looking back, 2023 was an incredible year. The whole Theater Doom Spiral song and dance was still blasting on repeat when the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes kicked off, landing those of us who still go to the movies squarely in the doldrums for half the year. Then there was that period when a bunch of big time studios thought it would be a good idea to pour money into streaming services while jettisoning any programming worth a damn. The strikes ended, the people who actually create the things we enjoy got what they wanted, and somehow we were rewarded, too, suddenly finding ourselves atop a glorious wave of prestige cinema. Shit was crazy. But, before any of this, in a year full of massive swings, BEAU IS AFRAID might have been the biggest.

On paper, it was any self-important film geek’s wildest dream: Everyone’s darling, A24, was bankrolling the hottest horror auteur’s passion project, starring none other than Joaquin Phoenix. The best part? No one had any idea what it was about! Now none of that exactly screams “commercially viable,” but A24 (probably banking on audiences still chasing the hypermodern high of EVERYTHING EVERYWHERE ALL AT ONCE) went for it. And, you know what, bless ‘em. As assured as HEREDITARY and MIDSOMMAR were, Aster’s third feature fully eclipses them; in spite of its title, BEAU is completely unafraid. The unreined imagination, the visual panache, the sheer, well, balls… Aster lays it all out in his first few moments as Beau navigates a parade of psychos and wonder of world-building to a therapist’s office where his inner world is crystallized in the telescoping hallways and towering presence of a childhood nightmare. Then, he finds out his mom died. Oh, and then he gets stabbed by a screaming naked man and hit by a truck. It’s all very Job-like, maybe that’s how best to describe it. But a life consumed by misery is shown to be only one path in one of the most wondrously beautiful sequences I’ve seen in a film, animated or otherwise. In the end, sometimes we have to laugh at our pain. ‘Cause hey, things could always be worse. [Joseph Simpson]

14. ANATOMY OF A FALL

Director: Justine Triet

“Sometimes a couple is kind of a chaos and everybody is lost. Sometimes we fight together and sometimes we fight alone, and sometimes we fight against each other.”

The steel drum 50 Cent cover. The Avocat général becoming a small-scale meme. A breakout performance for American audiences by Sandra Hüller. Can we be all that shocked that ANATOMY OF A FALL struck a nerve? In many ways, the types of films and even the aesthetics therein that regained popularity in 2023 harken to a different type of Hollywood altogether, from Nolan reinvigorating the stuffy biopic OPPENHEIMER to Gerwig’s Golden Age flair with BARBIE. Here, Justine Triet offers us the best courtroom drama in over a decade, tensely examining how one public moment will come to shape and define a person and their relationships forever. Triet tightrope walks the genre’s best tropes and forces us to be judge and jury, both with regard to the black and white nature of the case itself and the emotional gray area within. The result is, as Hüller says, an invigorating kind of chaos. [CJ Simonson]

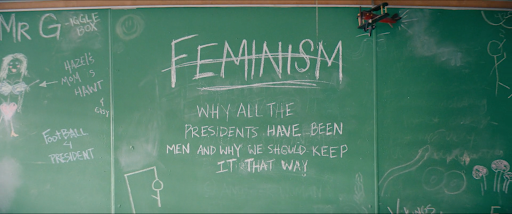

13. BOTTOMS

Director: Emma Seligman

I love a lot of things. I love going on walks with my dog, playing the same four-chord progression on guitar, and rewatching the TWILIGHT saga in the fall. But man, do I really love BOTTOMS. For someone who attended a small-town Texas high school in the mid-2010s, it holds a special place in my heart as the first movie I’ve seen in theaters that I felt also saw me. It’s a tale as old as time: Two gay teenagers, in an eternal war with the popular jocks, band together and start a girls-only fight club to ensure they can adequately defend themselves amidst the brutal social warfare of adolescence at an American public high school. Except not really, because they’re totally just doing it to get a chance to sleep with their dream girls. Bolstered by stellar performances from Ayo Edebiri and Rachel Sennott, our humble heroes pose as hardened criminals to gain street cred, use self-defense seminars to pick up girls, and prepare for a potential duel to the death with the football team. Okay so—maybe not a tale as old as time. Thank you, Emma Seligman, you brilliant person, for that.

BOTTOMS just gets it. There’s the idiocy of mediocre high school jock worship, perfectly showcased with the football team’s jerseys featuring each boy’s first name on the back. There’s the all-too-common blatant disregard for queer kids by school faculty, who hilariously and heartbreakingly refer to our dynamic duo as “the ugly, untalented gays.” There’s the oh-so-specific pain of falling in love with a girl that has a boyfriend who treats her terribly—and the ecstasy that follows that eventual first kiss. And, of course, there’s the extremely satisfying pleasure of watching NFL legend (and probable future Hall of Famer) Marshawn Lynch deliver lines like “You created a fucking fight club to get some coochie—and for what? Y’all don’t even know how to work that thing” with gusto. Still not convinced? Don’t take my word for it—listen to all-time NBA great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who recently called BOTTOMS “possibly the funniest movie of the year.” Kareem is a Hall of Famer, six-time NBA MVP, and six-time NBA champion. Coincidentally, he also happens to have immaculate taste in cinema. [Elizabeth Braaten]

12. JOHN WICK: CHAPTER FOUR

Director: Chad Stahelski

Opening on wall-rattling punches more bombastic than OPPENHEIMER’s nukes, David Lean homages, and an immediate dose of uselessly dense lore, JOHN WICK: CHAPTER FOUR swings its 5.5” dick out the gate with the gusto of The Girthmaster. Uh, don’t look him up. One of the great annoyances of JOHN WICK morphs into a genuine delight in CHAPTER FOUR, the team adroitly curating a time capsule of modern masculinity’s goofiness; when some bozo spits “second chances are the refuge of men who fail,” there’s enough of a silent lull afterwards that you’re expecting a sigma male jingle to kick in. The “mid-50s average guy” energy of this franchise is crazy, I don’t even know where to start and how to end! The tattooed rockabilly cutie phone line operators, bulletproof tailored suits, hotels considered as peak cosmopolitan centers, the Delacroix painting from Coldplay’s VIVA LA VIDA, life or death card games, family crests, German Shepherds, a mewing French boy as grandmaster antagonist, and this so far has been a conservative count of offenses. And yet, it’s this maximalism that perfects the experience. Despite its gargantuan scope, CHAPTER FOUR is where the series finally starts clicking, delivering the first great JOHN WICK film by trimming all the fat and letting you run rampant in the candy aisle until your teeth fall out.

John is a barroom brawler in a field of tactical lackeys, and Keanu being a lumbering old blob finally pays off when the character is textually exhausted: His peers are forced out of retirement, while he’s constantly being denied one for three hours. John keeps Wicking til he can’t Wick no more. The climax—a prolonged, hour-long homage to Walter Hill’s seminal THE WARRIORS—is uniquely infuriating in how it may very well be more exciting than the classic film it’s honoring. Is the “Nowhere to Run” cover complete ass? Absolutely, but after your 16th cheer in seven minutes, you let the clumsy flourishes bask over you. This was already a fantastic spectacle, but in its grand finale to end all grand finales, JOHN WICK: CHAPTER FOUR isn’t just content grueling its way to the top ropes as the one of the great pieces of action cinema ever made, but it must body slam on these hoes as a totemic ode to momentum itself.

It’s one thing to flaunt your prowess with the cinema—and we regularly reward this obnoxiousness graciously—but Chad Stahelski flaunts his performers’ choreography as a salute to the ephemera of action star blocking. It’s The Keanu Show, no doubt, but all of these stunt performers are feeding their reels with crisp, full range movement. Not a single hit is wasted, and you will sit and relish in what these hall of fame meatheads can do to each others’ bodies. The world of JOHN WICK feels heaps better when you enact fluid combat scenarios within it instead of erecting fisticuff scaffolding around a rulebook. The bittersweet mark of great action cinema is it opens your eyes to how awful most of the crop really is, and JOHN WICK: CHAPTER FOUR is a definitive bar-setter. Too long? Go fuck yourself. Let the boomer cringe flow. [Kevin Cookman]

11. SALTBURN

Director: Emerald Fennell

I try my best to go into movies knowing as little as possible about them, and SALTBURN was no different. I was peacefully ignorant heading into the dark theater, cherry vanilla Coke Zero and large popcorn in tow. I knew that it starred GQ Movie Star of the Year-slash-certified babygirl Jacob Elordi, the supremely talented Rosamund Pike, and that interesting looking guy from THE BANSHEES OF INISHERIN whose name I couldn’t remember. (Sidenote: I guess there’s a last time for everything). In fact, the most important piece of pre-viewing knowledge I had of the film came to me courtesy of my girlfriend, who, after reading an article in British Vogue about the nostalgic Y2K style showcased in the movie—and the William and Kate episodes of the final season of THE CROWN—eagerly informed me that noughties uni fashion was finally making its long-anticipated comeback. In my blissfully naive state that afternoon at the Saturday matinee, I believed I was about to get swept up in some English high society, royal family-adjacent early aughts romance. Man, was I wrong.

Admittedly, SALTBURN’s vibrant first hour aligned perfectly with my cloudy expectations, meaning it had me in a tight-fisted chokehold. The clothes! The glamor! The rich English people! I embarked on my first bathroom break fully convinced that I was bearing witness to my generation’s PRIDE AND PREJUDICE. But again: man, was I wrong. And to tell you the truth, I’ve never been so happy to be so. The bathtub scene! The period scene! The gorgeously twisted, Gen Z-TALENTED MR. RIPLEY of it all! And don’t even get me started on that grave scene, one that had me in fits of laughter and proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back of a young couple seated in the theater’s fifth row, who decided they’d had enough, thank you very much, and walked out in the middle of. When Harry Styles voiced his musings on go-to-the-theater film movies, he probably didn’t have this one in mind.

In anticipation of this blurb, I sat down to watch SALTBURN again. Safe to say, my second time around wasn’t nearly as shocking, and I found myself crafting elaborate imaginary arguments in my head with those who couldn’t stomach the film, who found it too raunchily grotesque to finish. But it was then, during the heat of one of these fictional arguments, that I had a breakthrough: we now exist in a post-SALTBURN world. For a generation of young people, this will be remembered as a film that adeptly showcased social climbing aspirations, challenged traditional expectations for storytelling, and solidified the upward career trajectories of a number of budding film stars. It’s also one that proved to be that rare, efficient jack-in-the-box for information-age tough crowds, who, having seen everything, are oftentimes burned out and unable to be surprised by just any old clown popping out of a bright plastic cube. Thank you, SALTBURN, for managing to shock us in 2023, for your imagination and originality—and, of course, for that final scene. [Elizabeth Braaten]

10. GODZILLA MINUS ONE

Director: Takashi Yamazaki

As the credits rolled on GODZILLA MINUS ONE, so did a wash of unexpected tears on my face. My experience with the Godzilla films, and monster movies in general, have mostly been of the Americanized variety where the military-industrial complex is called in to save the day with all the bombs and explosions you expect from a mid-2000s action flick. However, shortly before I viewed GODZILLA MINUS ONE, I caught the original 1954 version to give another perspective to my conflicted feelings about the narrative in OPPENHEIMER surrounding the Japanese. This is where I learned about the real origins of Godzilla, serving as a poignant allegory for the atomic horrors that seared Hiroshima and Nagasaki into the global consciousness, with an intriguing subtext interpreting Godzilla as a metaphorical embodiment of the United States: a colossal force inadvertently awakened, unleashing its fury upon Japan.

After seeing so many American films depicting how much force is needed to take Godzilla down, this irony was not lost on me. But GODZILLA MINUS ONE delivers a different approach to defeating the monster as we watch the military try and fail time and time again to defeat their nemesis. It’s everyday citizens coming together for the collective good that ultimately succeeds in their mission and a hope that, even if their plan fails, they all had hope—a hope that was once thought lost during nuclear fallout. It’s a refreshing message to see right now as our world is ravaged by war, and people are calling to their governments for help that is seemingly falling on deaf ears. GODZILLA MINUS ONE is a true return to its intended form, and the modern additions to the visual spectacle are stunning. The bottom-heavy Godzilla traipsing through the city and toppling skyscrapers calls back to its original, and his heat ray had me gasping and holding my chest. But the little moments between people and the raw emotions they share so vulnerably make this film so special, as we spend more time watching an introspective story of grief, survival, and shame in post-World War II. If while watching OPPENHEIMER, you wish they had given more of a POV to those who survived the bomb after it dropped, GODZILLA MINUS ONE fills the void. Who knew a creature feature could be so human? [Lauren Chouinard]

9. THE ZONE OF INTEREST

Director: Jonathan Glazer

The German word for bleach, bleich, meaning pale, is derived from the Proto-Indo-European bhel-, which means to shine or burn. Preserved in Jacob Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology, it is lent to one of Death’s many names: Der Bleicher, so called for what he does to bones. THE ZONE OF INTEREST, Johnathan Glazer’s portrait of a dutiful Nazi family, makes plainer still the link between sanitation and death. Boots are removed and washed before entering a home where servants keep busy with broom and mop. Crisp white sheets are hung in such a way as to further obscure walls we must never see behind. The work never stops, no matter how much they clean. Preserved also by Grimm was a tale we all know, one Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Höss reads to his children as ghastly orange light licks their bedroom window: Hansel and Gretel. So were the ovens into which countless souls were driven prefigured by a children’s story. In THE ZONE OF INTEREST, past and present aren’t so far removed. It is a place where, try as one might, stories, words, ideas don’t simply go away. As a formal exercise, it is unimpeachable; the dispassionate precision of UNDER THE SKIN here emulates the methodology of the Nazi death machine to a nauseating degree. Narratively, it is a void. There is little in the way of character development or anything so prosaic as plot to serve as guide. From the end of a hallway or other side of a room we look in on a life built upon the systematic annihilation of others.

Glazer has said this film is “not a Museum Piece” as some perhaps unsure how to receive something that so thoroughly eschews convention have decided. It is an angry, vital work that demands to be seen. If Johnnie Burn’s thrum of rolling stock, cries, and gunshots gnaws at the edges of the Höss’ closed little world, Mica Levi’s gut-wrenching score emerges to shake its foundation. Through the lens of a FLIR camera, a Polish girl—12-year-old Aleksandra Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk—hiding apples for prisoners becomes a literal beacon of warmth in a cold dark night. Often it is asked how the Holocaust could have happened (a curious skirting of how it could have been prevented). Many seem to have forgotten or never known that Hitler became chancellor through legitimate political process. People voted for the Nazi Party out of economic self-interest. Today, on platforms the despots of yesteryear could only dream of, in evil’s very tongue, again politicians refer to opponents as “vermin” and immigrants as “poisoning the blood of our country.” Even if they won’t say it aloud, an alarming number of people are okay, if not happy, with the suffering of others if it means a shot at getting what they want. It shouldn’t be any wonder, though: look at any household cleaning product. Chances are it says something like “kills 99.9% of germs.” Language shapes the way we view the world, after all. But in the film’s boldest moment, time itself is done away with, as we bear witness to the quiet dignity of those who clean not to erase, but to preserve. So that the stories of all those lost are told. So that we do not forget. [Joseph Simpson]

8. PRISCILLA

Director: Sofia Coppola

Once again, Sofia Coppola has created a portrait of the frustrating loneliness of teenage girlhood through her specific style of costume and production design. Yes, PRISCILLA is the true story of an American princess from her perspective, but it’s also very much a Sofia Coppola romantic drama. Clothing tells the story of Priscilla’s development from innocent schoolgirl, to ‘60s Hollywood siren, into a woman of her own making. Sweaters, skirts, sweet dresses, and, of course, her Catholic schoolgirl uniform are swapped out to run with Elvis’ crowd—and to please him. Elvis dressed Cilla up as his doll, taking her on shopping sprees to make this child look older, more sophisticated.

It’s easy to witness Priscilla’s story and think “Girl, you’re a victim!” but, for her, it’s more complicated than that. It’s more difficult, but perhaps more honest, to come to terms with both a girl who was groomed by a powerful man 10 years her senior and as a woman with a conflicted heart—in love with a doomed man and desperate to become her own person at the same time. No longer the innocent schoolgirl Elvis met in 1959, Priscilla learned how to operate under the manipulative framework Elvis built, learned how to make it work for her, even after he started throwing chairs and sleeping around. Elvis sought to control her as he lost control over his own life—Priscilla saw his struggle, and wanted to help him, until she realized Elvis’ meteoric destruction would end her life, and her daughter’s, too. This transformation may seem quiet, but it’s there, and eventually led to a departure from life on the hill, as they once called it. There’s a scene where Elvis picks a volatile fight with a pregnant Priscilla, threatening to kick her out. As a young girl, she would have kicked and screamed, longing for her beau’s affection. “Just tell me when to leave,” adult Priscilla coolly replies, not falling for his manipulative bullshit anymore, knowing that neither his tender embrace nor his harsh words can affect her any longer. [Katarina Docalovich]

Read Katarina’s full review here!

7. BARBIE

Director: Greta Gerwig

It’s easy to forget now, but getting swept up in BARBIE-mania this summer was so gratifying. It was the first time in a very long time where it felt like a movie was central to the monoculture and had spawned a new universe of memes. In the midst of the entire entertainment industry burning to the ground, seemingly just so a handful of studio heads could paper over their failures to make streaming profitable, it was an absolute joy to experience millions of people remembering how special going to the movies can be.

But let’s not forget what BARBIE is actually about, which is transcending the limitations of gender roles to become a fully realized human being. Margot Robbie’s stereotypical Barbie goes on a personal odyssey in which she is plagued by irrepressible thoughts of death, which leads her to journey to the “real world” beyond her comfortable, hollow existence in Barbieland, and when she arrives in the real world she is confronted by a reality that is far messier than her presuppositions: a world where the invention of Barbie did not in fact liberate and empower all women. She’s forced to reckon with her preconceptions as she returns to Barbieland to stop Ken from destroying Barbieland with Patriarchy. She does, by getting Ken to love himself rather than the untouchable ideal of Barbie. Only when she teaches her shadow self-acceptance is she able to admit what she truly wants for herself, which is to become mortal. When you type it out, it’s absurd what a Greek tragedy this toy commercial really is.

We all live with irrepressible thoughts of death now. We all know the party will have to end eventually. Barbie represents a childlike state of innocence that we have to outgrow to become fully human. By having Robbie’s Barbie make the choice to be flawed and mortal, Gerwig gave her audience permission to age, to die, to experience the full gamut of human emotion rather than remain trapped in an idealized fantasy forever. In a country where large portions of the population exist in a fantasy realm awash in comforting IP, Gerwig’s ability to make her audience embrace their mortality felt like the most thrilling thing she could possibly do with the assignment. The movie’s actual feminist politics might fall apart on the slightest bit of analysis, but the core emotional crux is what ultimately hooked audiences and made this the juggernaut that it was. Yes, the Oscars discourse about the film has been embarrassing for everyone involved, but the Billie Eilish sequence is going to define the decade. [Carter Moon]

6. ASTEROID CITY

Director: Wes Anderson

As I lay on the ground surrounded by fellow Wes Anderson appreciators, all of us patting our stuffed bellies o’er the incredible “50 point game”-esque run the good ol’ Texas director had this year, the mind reels. I begin to think about coming to terms with several bullet points. His current run’s skyscraper-leveled layers of disambiguation and contextualization for themes of nostalgia and existential ennui has unlocked more experimental toys, tools, and vernaculars to excavate complex, universal feelings of depression in ways other contemporary artists need maybe even a lifetime to pull off themselves. One could begin to approach his magic not by setting some fancy clothed weirdos slow-motion running to “This Time Tomorrow” by the Kinks—as every single Wes Anderson parody would urge you to guffaw at as though it’s all he’s capable of, and that all you’re capable of grasping is something as surface-level as such—but by looking at the physical craftsmanship on display. Yes, his army of contractors and designers are playing to a very specific unified vision, but it can be difficult pointing in another direction to equally creative, heartfelt, non-phony, and gorgeously rendered output in today’s cinematic landscape, no matter what the studio tries to sell you.

His editing has become snappier and unpredictable, helping underline his signature deadpan punchlines as well as devastating one-liners delivered by all-too-game ensemble members who seem happy to get in the sandbox with Anderson. The whiplash he’s able to achieve often urges audiences to look above and beyond traditional cinematic language for something riskier, but oft-richer. This past decade I’ve quietly prayed that we’d get another BOTTLE ROCKET-style shaggy-dog romp from Wes, but going from THE FRENCH DISPATCH to ASTEROID CITY to his Roadl Dahl shorts revealed intricacies in what he has to offer, and even reminds me of what I fell in love with in the first place from the author of THE ROYAL TENENBAUMS, THE LIFE AQUATIC WITH STEVE ZISSOU, RUSHMORE, FANTASTIC MR. FOX, et al. He continues to give us soulful “Capital-C Comedies laced with toothy angst and life-affirming ruminations on what we cannot control, and what we try to in the wake of this understanding. To cope is noble, and unearths our deepest selves in the most embarrassing and astonishing ways all at once. This is Wes Anderson, bitch! We clown in this mother fucker. Best take your sensitive ass back to… uh… most A24 movies? [Rocky Pajarito]

5. HOW DO YOU LIVE? (aka, THE BOY AND THE HERON)

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

If we’re going to be talking about directors releasing career masterworks in their twilight, we must be keeping Hayao Miyazaki in the same conversation as Scorsese (Leo apparently introduced Scorsese to SPIRITED AWAY and PRINCESS MONONOKE, but that might just be Marty humoring the guy). Made during an arduous seven years, with Miyazaki coming out of his third retirement and beleaguered by both the pandemic and the death of legendary Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, it is a miracle that HOW DO YOU LIVE? (aka THE BOY AND THE HERON) even exists. There seems to be an implicit desire for Miyazaki to buck against his own tropes here. The sullen but forthright protagonist Mahito contrasts with his usual focus on precocious adolescent girls—continuing the autobiographical streak that he started doubling down on in THE WIND RISES a decade ago. Our hero’s call-to-action and journey into the isekai fantastique is not accomplished by crossing a literal threshold but by an act of self-harm. Dreamscapes and dream imagery abound, strengthening the idea that everything we’re seeing on screen may just all be a fantastical hallucination. The soot bunnies are replaced with milky white Warawara cum sprites. Jovial cartoon grotesquery that is rendered delightful in his earlier films spills into the horrific here. Mahito pierces a fantastical fish with a pocket knife and the entire contents of its guts spills out like a magician pulling infinite silk from his sleeve, enveloping the young lad. PONYO this is not! Each new realm that Mahito submerges himself into seems to have a direct artistic or painterly reference in the sumptuous, jaw-dropping backgrounds. This is something akin to if Dante’s Inferno was about traveling back in time to hang out with your dead mom.

Mahito enters the multiverse about three quarters of the way through this film, and I couldn’t help but dwell on the fact that people are seriously putting this film in contention with ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE—a movie that seemed partially unrendered upon release, getting subsequent patches like many games made under brutal crunch. Miyazaki’s workrate on previous films was an average 10 minutes of animation per month, and that slowed to one minute for the production of this film. The painstaking process produces palpable results: you can feel his soul in every gorgeous frame. The master surveys the younger generation from a lucidly unrelenting perch, ultimately coming to the conclusion that these kids will figure it out on their own after all. The self-reflection and pathos have led many to assume this is Miyazaki’s swan song (pardon the awful bird pun), but much like the contradictions inherent in this film—the spit, vinegar, blood, sweat, tears, cum sprites, and bird shit—it also suggests Miyazaki still has more in him. It’s there in the very title of the Japanese release. We have a better idea of how Hayao Miyazaki keeps living. He’s still drafting Nausicaä sketches and thinking about what’s next. Still iterating, deepening, the themes and contradictions that were always inherent in the work. Our great-granduncles still may yet have lessons to teach us. [Luke Phillips]

4. POOR THINGS

Director: Yorgos Lanthimos

What makes Yorgos Lanthimos unique in modern cinema is his ability to build elaborate sandboxes for his actors to play in, giving them space to do things on the silver screen that few actors get to do outside of black box theaters. POOR THINGS is a revelation first and foremost for simply allowing Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo to be absolute feral freaks on a level previously unseen. Watching Bruce Banner get so horny that he puts himself into an insane asylum is deeply satisfying. Emma Stone will be synonymous with her performance as Bella Baxter for the rest of her career; the richness of her progress from adult baby to French prostitute to shrewd mad scientist is something acting students will study for generations. After seeing cinema’s edges get completely smoothed down, seeing a dark science fiction satire of human sexuality is pure oxygen injected into a dying ecosystem. We can debate endlessly about which of the sexual relationships depicted in POOR THINGS is ethical, if Lanthimos is sufficiently viewing these relationships through a feminist lens, or if Lanthimos was really just ripping off Frank Henelotter’s FRANKENHOOKER, but at the end of the day it was just such a joy to be able to have these conversations about a Searchlight Pictures release from 2023.

And of course, POOR THINGS is more than just the funny, gross-out performances from its stars. This FRANKENSTEIN-meets-Pygmalion tale dwells on the limits of scientific progress, the bizarre ways we’ll punish each other and ourselves in the name of love, and who exactly gets to profit off of our labor. In a funny moment of cultural serendipity, the story about a mad scientist who puts the brain of an unborn baby inside her dead mother’s skull to revive her as his own surrogate plaything ended up serving as the perfect bizarro yin to BARBIE’S yang. The film is a steampunk vision of the 19th century presented with a heavy dose of nitrous oxide and laudanum. Lush, practical sets are contrasted perfectly by surreal CGI backdrops. Lanthimos’ precise command over a fisheye lens pairs perfectly with Jerskin Fendrix’s uncanny, elastic score. What’s perhaps most thrilling is how Yorgos manages to zig where you expect him to zag. There’s a strange tenderness, a warmth about the human condition, that’s been missing from most of his work up until this point. It’s the kind of sumptuous film we rarely get to take in these days, the kind of film that sends you scurrying to IMDb as soon as the credits roll so you can learn more about every artist involved in crafting it. And above all else, it made me laugh harder than any movie has in years. God bless Yorgos. [Carter Moon]

3. MAY DECEMBER

Director: Todd Haynes

Todd Haynes’ belly-knotting MAY DECEMBER attacks our culture’s obsession with sensationalizing other people’s business, exposing a darkness within us that we cannot shake. For the two-hour run-time, the story played with my expectations and desires from start to finish. I didn’t know who to love, who to hate. I couldn’t gauge when it was appropriate to laugh or to cry. The classic give and withholding of information is one of the best teases I’ve experienced of the year, providing the narrative stronger power over all who’ve watched MAY DECEMBER. Netflix has the film listed under its “Drama Movies” genre category, but the Golden Globes had the film nominated among “Best Motion Picture Musical or Comedy,” which many critics and journalists ate up—as did I. Natalie Portman’s performance as actress Elizabeth Berry was so sensually pervasive, painfully corny, and a little deranged that it gives the film this endearingly campy quality that truly makes the argument of the film all the more poignant while still keeping an satirical edge. What truly twisted the knife is the development of Elizabeth’s corporeal involvement with taking on her portrayal of Julianne Moore’s Gracie. Haynes’ way of exposing the filmmaking process as the backbone of the narrative was so grotesque I couldn’t help but chuckle at what directions the leads must’ve been getting in order to capture those top moments of their performances (“It’s starting to feel real”). As we all know, acting is a bodily job, inherently, but something about it in MAY DECEMBER had me hyper-fixated in a tight wince.

The film’s take on senstonalization and exploitation of victimhood really made me queasy, too. Charles Melton’s performance as Joe is painfully passive; I couldn’t help but see him like a confused lost puppy. That so many heavy-handed elements in the subtext expressing Joe’s subconscious are so on the nose further emphasizes this unshakeable camp that trails the film’s reputation. It’s thrillingly unknowable. Joe and Elizabeth? My guts were left churned. That man cannot tell the difference between being seen and understood versus being observed and studied. Wrenching, heartbreaking, nearly puked. I can’t write this without addressing some of the resulting backlash the film has received by those who were involved in the real case. All of that noise is a direct consequence of what we as a culture have done with a story and experience that has been taken away from the perpetrators, witnesses, and victims involved for our own entertainment and pleasure. Regardless of how stories like this make us feel, we love it, and it’s repulsive. We can’t help it. [Valentina Pagliari]

2. OPPENHEIMER

Director: Christopher Nolan

Midway through Christopher Nolan’s OPPENHEIMER, there is a stunning silence as we approach finally witnessing The Bomb go off. In this moment, so many crucial elements of the film are working in tandem—Cilian Murphy and Josh Peck’s anguished anticipation as Oppenheimer and Trinity director Kenneth Bainbridge, respectively, alongside dependably mythic cinematography from Hoyte van Hoytema, sublimely illusory cutting from Jennifer Lame, and the most assured directing of Nolan’s career create a tension that can only be described as magic. You feel as if the world may end in that second, that the sky may actually be set aflame just as Einstein feared. A giant train is barrelling towards the screen and the audience might as well be ducking for cover. Even after being granted the catharsis of the glorious fireball that follows, we are still left feeling the world has been forever changed. I was not expecting this kind of knotty, resonant work coming from a director I had previously thought of as something of a neo-vulgar auteur. Christopher Nolan thoughtfully and sympathetically depicting the most brilliant American Jewish and Communist brainiacs this side of Tin Pan Alley was not on my Bingo card. The approach here is noticeably different and refreshingly bold, with a first person screenplay and subjective/objective filmic conceit that portrays Oppenheimer’s slipstream protagonal consciousness in glorious IMAX color: the brutal, rigid bureaucracy of interrogations and Senate hearings in probing, pointedly political black and white. In some ways, DUNKIRK, TENET, and OPPENHEIMER work as a trilogy—one of the only true blockbuster auteurs of our age recontextualizing his preferred hyperfocuses to increasingly astonishing and expansive results.

In recreating blockbuster thrills in this biopic’s trappings, Nolan relies on bombast. Pushing every gorgeous frame to its limit, the New Mexican desert is rendered as remote and all-encompassing as the twin desert planets Arakis and Tatooine. I’ve long had to differentiate movies in terms of quality like how one differentiates Taco Bell from a healthy balanced meal. There have been so many fake-ass movies this past decade (most of them produced purely to exploit IP) that the presence of a real-ass movie not only existing, but becoming as big of a hit as OPPENHEIMER has seemed like an oasis in a literal desert. For a brief moment, in the headrush of all the Barbenheimer meme-ery, I felt optimistic about the future of going to the movies. Everyone was out in their Barbie pastels seeing this real-ass movie and having a great time. Then, like clockwork, the discourse cycle began anew, and Nolan was accused of racism online for not having a ghoulish Godzilla-esque nuclear holocaust sequence depicting hundreds of thousands of innocent Japanese civilians getting murdered by an imperialist war machine. Six months later, we had all moved on, as our imperialist war machine continued to fund more genocide. [Luke Phillips]

1. KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

Director: Martin Scorsese

When we first meet Mollie Burkhart (née Kyle), she is listing the names of the already dead Osage members who perished under suspicious conditions with no investigation. Even before her own family members are cruelly picked off one by one by William Hale, Mollie has been searching for answers. Her face is full of aristocratic coolness, not haughtiness, as she is forced to account for each of her financial decisions to a white banker, as she only has restricted access to her own fortune for transparently racist reasons. Mollie’s confidence in herself and in her people is steadfast, both in the face of this absurd racism, and later, unspeakable violence against her family. Since this is a Scorsese historical epic, this tapestry is woven full of stellar performances one could point to—Cara Jade Myers’ fiery turn as Mollie’s older sister Anna and singer/songwriter Jason Isbell’s stoic strength that he adds to the character of Bill Smith are two of my favorites—but it’s Lily Gladstone’s picture. Just as Sharon Stone not only held her own against, but also outshone Scorsese heavyweights Joe Pesci and Robert De Niro in CASINO nearly 30 years ago, Lily Gladstone does so here with her powerfully wise performance as Mollie Burkhart. Mollie’s natural born grace, which would not be possible without Gladstone, stands up against both Ernest Burkhart’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) pathetic loser frown, and his uncle Hale’s wolfish grin (De Niro once again). Mollie’s gaze cuts right through their greedy bullshit more than she even realizes, whether she’s in a playful mood or a severe one.

Together, Lily Gladstone and Martin Scorsese have challenged wider audience expectations for what a Scorsese picture looks like, a feat he has pulled off at each new stage of his career (and the man makes it look easy!). Maybe David Grann’s non-fiction best seller didn’t seem like the most obvious choice for a Scorsese adaptation at first glance, but the man has been examining the roots of American corruption, greed, and explosions of violence since he first began his decades-long career, so it made sense to those of us who were already aware that a Scorsese movie doesn’t always equate to a traditional New York gangster picture. The choice to veer away from Grann’s source material by centering Mollie’s experiences instead of those of Tom White (Jesse Plemons), the man who cracked the case, was a welcome one, if a little more unexpected. It’s Gladstone’s smash performance, as well as Scorsese’s own acute awareness of his own ambivalence toward being the one to tell the story of this painful chapter in Osage history, that elevates KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON above all the others. Living in an age when we can witness new Scorsese pictures in the theater is a privilege that will not last forever, no matter how much we collectively wish that were possible. [Katarina Docalovich]

Comments