Celebrating its 55th anniversary this year, Jean-Luc Godard’s PIERROT LE FOU is among The Criterion Collection’s prestigious new releases this week. One of Godard’s most iconic films, PIERROT LE FOU is a relic of Godard’s career and his transition towards including more evident socio-political commentary as seen in many of his films in the late ‘60s onward. A cross between a romance and a gangster movie, PIERROT LE FOU tells the existential love story of what Godard calls “the last romantic couple.” Along its own self-reflexive journey, the film calls on its viewers to ask daunting questions about our existence, and contemplate the interrelationships between art, love, life, and death.

PIERROT LE FOU is a tale about a rekindled romance between Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and Marianne Renoir (Anna Karina) as they run away from the bourgeois society of magazine ads and corporate squares. After run-ins with unwanted visitors, the two embark on a BONNIE AND CLYDE-like adventure that Marianne describes as their very own “gangster movie” full of whimsy and excitement. The film adopts a self-reflexive nature as it plays, suggesting an awareness of itself and puts the idea of mimesis (i.e. art imitates life) into question. As an arguably highly representational medium of art, film had been (and continues to be) used quite directly and often literally to expose reality. By the 1960s, and as practiced by French New Wave filmmakers, this notion became obliterated by the avant-garde and the clear manipulation of the medium of film itself making it more impressionistic rather than representational. This idea is established at the start of the film when Ferdinand is reading to his young daughter about Baroque painter Diego Velasquez and his later works that pursued the more abstract subjects of “evening, of open spaces, and of silence.” Ferdinand too is seeking out the absurd, something other than what he currently knows.

Ferdinand’s bourgeois wife is his antithesis. The couple lives in an upper-middle-class apartment, their bedroom adorned with embellished wallpaper and furniture. His wife, an Italian woman with money, is a sheep among the herd in the post-modern consumer-capitalist society. Flaunting her new invisible Maidenform girdle, she is vulnerable to the commercial next-best-thing. An insert of an ad for the girdle appears under a voice-over of Ferdinand announcing “after Athens, after the Renaissance, we are now entering the civilization of the ass.” Against Ferdinand’s wishes, the couple attends a party at the wife’s parents’ house. Guests are overheard talking about new products like living advertisements: men and women talking to themselves about the look of the new Alfa Romeo, the fresh feeling of wearing Odorno deodorant, and the silky blonde hairs thanks to Aqua Net, etc. Ferdinand stands out against the backdrop of stagnant bourgeois society. He’s the only body that moves across each shot while the others remain stuck within the frame, locked into the backdrop. Being among these “squares” makes Ferdinand question his own existence and complacency in this society. He finds himself next to a lonely American filmmaker who is in Paris to make a movie who explains that cinema is “a battleground” full of “love, hate, action, violence, death.” He says in one word that cinema is “emotions,” which sets up the existential goal for the narrative that is beginning to unfold. He returns home and finds Marianne, the babysitter, asleep and in need of a ride home. The two drive off and so their journey begins.

Marianne’s last name “Renoir” references the pioneer of Impressionist painting, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, suggesting a direct nod to the idea that the film medium is being used impressionistically in this film. Upon her introduction to the story, she brings Ferdinand and the viewer out of the banal world of materialism and into an abstract world of feelings as she sings about her love for Ferdinand and scolds him for talking to her with “words” while she looks at him with “feelings.” The crux of what is sought after in PIERROT LE FOU comes down to how we identify with our existence. Ferdinand keeps a notebook on him and maintains a steady routine of reading and writing on a constant search for an understanding of the meaning of life. He underlines a passage that reflects ideas that stem from Berkeley’s philosophy that to exist is to be perceived. The passage reads: “I enter the room. That is when I really start to exist for you. But I existed before that. I had thoughts… So the problem is to show you alive, thinking of me and at the same time, to see me alive, by virtue of that very fact.” While he and Marianne are together, they validate each other’s existence. In the brief moments when they acknowledge the viewer, whether by breaking the fourth wall or by aesthetically reminding the viewer that they are watching a film and not experiencing reality, they validate the existence of the viewer too.

Along their journey, Ferdinand is looking for a subject for a novel. He explains to the audience that rather than writing about the lives of people, why not write about “life itself, what lies between people, space, sound, and colors?” This shifts the perspective of the film to focus on the question of what is “life itself.” He comes to realize that people believe the only thing of any interest is “the road people follow” and that once the road is identified and people understand who they are, everything else is neglected as a mystery. He says “that mystery, forever unsolved, is life.” Marianne suggests another story idea about a man who is running away from Death until it catches up to him. The idea of death is heavily present in the narrative. In its early scenes, a quick insert shows a poster that reads “Rendez-vous with Death.” As the film progresses to this point, we come to realize this story is just another interpretation of life itself and that the plot of PIERROT LE FOU is, too, another interpretation of life itself.

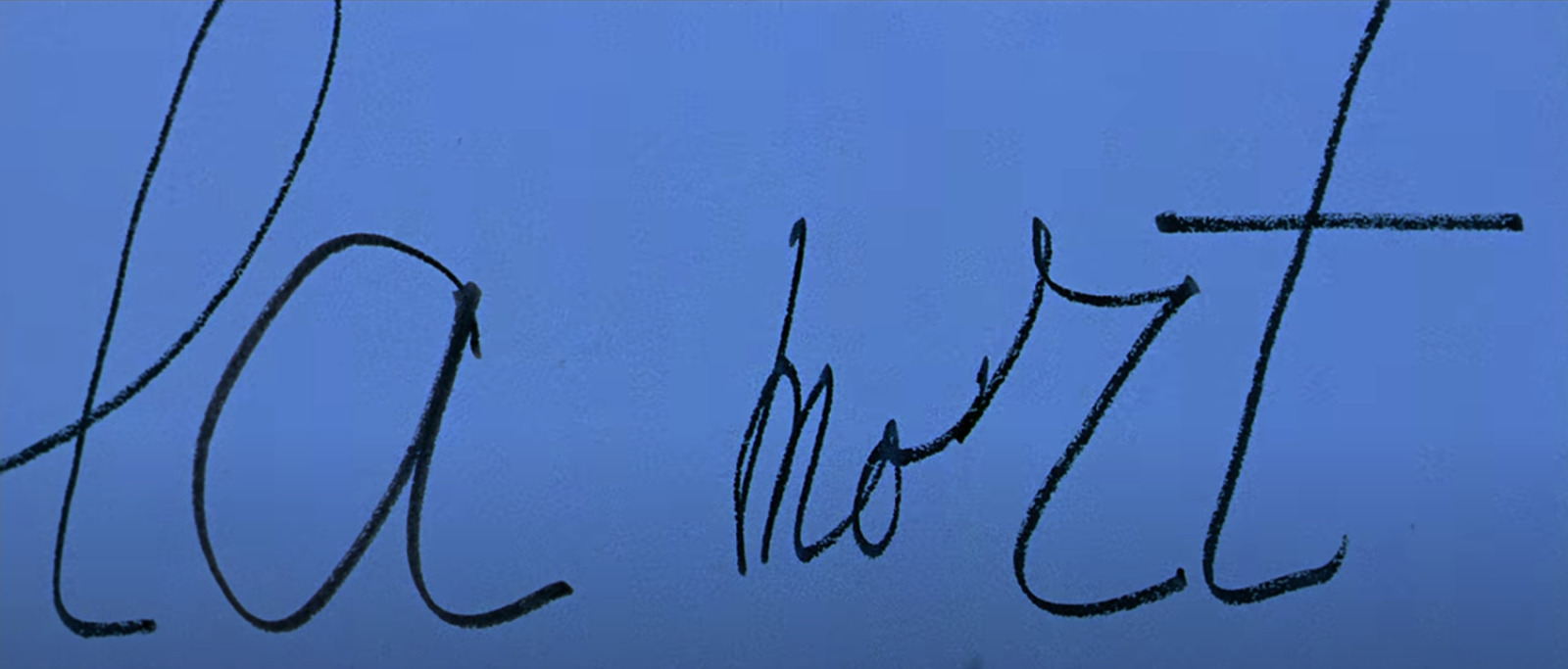

The ending is as existentially nihilistic as it is ironically comical. After a shootout with a group of gangsters results in Ferdinand shooting Marianne, Ferdinand decides to paint his face blue and blow his head up with dynamite. As he prepares for his big dramatic exit, an insert of the letters “la rt” which spells out “art” is quickly filled in to spell out “la mort” (death). This immediately correlates the idea of art and death that had been in constant discourse with each other throughout the entirety of the film. It leaves us with so many more questions than we came in with. Is life just a manifestation caused by the ideas of art and death? Is life just a constant performance art that we exhibit until our death? I don’t know, I don’t think Ferdinand or Marianne knew, and I for sure don’t think Jean-Luc Godard knows either. Whatever life is or isn’t, PIERROT LE FOU will keep us guessing until the end of time. But until then, we can keep making art searching to solve the mystery that is life itself.

Excellent review!!