2021 was an odd year of transient, nigh-unidentifiable cinema: leftovers meant for an alternate 2020, knee-jerk responses to the ongoing crises of the past two years, and stories conceived in a world that no longer resembles or functions as our own. Nevertheless, the Merry-Go-Round Magazine staff was able to make sense of the mush, and hereby present the Top 21 Films of 2021.

21. ZOLA

Director: Janicza Bravo

I like stories where you’re locked in a hurricane of the characters’ poor decisions. I honestly find it relaxing, like I’m watching it all from the eye of the storm. An infamous Twitter thread inspired this brisk, 90-minute film, and the result is an unfiltered, alluring fever dream. Two sex workers go on an odyssey from Chicago to Florida to make top dollar stripping at a high-end club, but it’s a false flag for things to go really wrong, really fast. The journey is at first zany, then ultimately dangerous, as the titular ZOLA is tricked into a trafficking scheme. Bravo takes us through the various settings of down-and-dirty Florida hospitality from the perspective of a sex worker: a humid, dim wasteland dotted with nameless motels and desperate johns. ZOLA’s female leads are portrayed and written with empathy instead of exploitation. Taylour Paige’s Aziah “Zola” King, the original author of the Tweet thread that inspired the film, navigates her dark and uncertain fate with a skillful wit and humor that few could emulate. Equally, Riley Keough as her frenemy, Stefani, responsible for luring Zola into this mess, elevates what begins as a Bhad Bhabie impression and actualizes the character into a depressingly authentic party monster. Keough’s Stefani is absolutely off-the-wall at times, but that’s why it’s an amazing performance–Keogh goes for it, and the result is, in the actor’s words, “an inappropriate nightmare.”

The twist and turns of ZOLA feel at times like neo-noir, then a comedy, and then some sort of surreal art project peering into the soul of contemporary society all while blasting “Hannah Montana” by Migos. It’s a romp through late-stage capitalism that deconstructs the supply chain of sex work in hilarious and absurd ways. If I was going to attempt to fit the ZOLA aesthetic into a genre I’d probably name it motel-sultry– a captivating, blue-hued adventure where the tension is high and the cops could get called to break up the party at any minute. It’s in the company of UNCUT GEMS, TANGERINE, or BODY DOUBLE where you’re a voyeur to some down-and-out people really trying to do the best they can, with the little bit of savvy and cash they got. [Hilary Jane Smith]

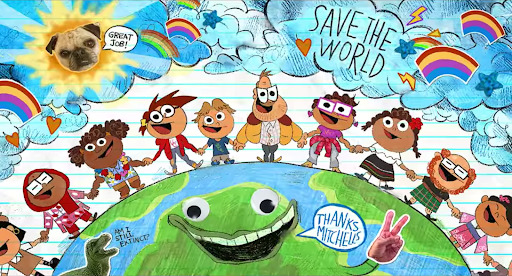

20. THE MITCHELLS VS. THE MACHINES

Director: Mike Rianda

Admittedly, THE MITCHELLS VS. THE MACHINES is kind of built to quietly slide on to critics’ end of the year lists. It’s Film Twitter’s equivalent to the Oscars loving movies about making movies—sometimes we like seeing stories about ourselves. And when the DVD menu of a children’s film is built to mirror that of a Criterion release, a solid argument could be made that GRAVITY FALLS alum Michael Rianda has cheekily lost the plot a bit, making a film as much for Letterboxd reviewers as your 12-year-old niece. I can’t speak for children—perhaps a giant Furby Kool-Aid Man’ing through a wall and screaming “I will avenge my fallen children, let the dark harvest begin!” is something they, like me, found hilarious. But at its core, THE MITCHELLS VS. THE MACHINES is playfully regurgitating decades of stories about father-daughter relationships, family vacations, and growing up as outcasts, and successfully giving them a modern polish. It’s familiar, yet fresh, and the visual language and style, something of a continuation from SPIDER-MAN: INTO THE SPIDERVERSE, successfully buries tons of Easter eggs and jokes in the background. At the end of the day, someone’s 12-year-old niece will one day become the next Brat Pitt of Letterboxd. In its own weird, specific way, this movie is for them. [CJ Simonson]

19. THE DISCIPLE

Director: Chaitanya Tamhane

Chaitanya Tamhane’s THE DISCIPLE, an Alfonso Cuaron-backed drama about a young man struggling to find his voice in North Indian classical music, is the most criminally overlooked film of the year—a film buried by Netflix in spite of it quite possibly being the best film about the artistic process. It’s excellent filmmaking precisely because its superbly unique milieu and realist approach are secondary to the universality of its spiritual teachings. THE DISCIPLE could just as well be a film about an overly academic artist failing to understand the nuances of the Delta blues. It’s not a film about Hindustani classical music as much as it is a film about artistic existentialism, Indian or not. [Sergio Zaciu]

18. THE HAND OF GOD

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Fellini’s indelible influence looms large over Paolo Sorrentino’s latest exercise in lust-for-life pageantry. Not only is Il Maestro himself namechecked as one of the many great icons who peripherally pass through the protagonist’s childhood town, but THE HAND OF GOD itself is best described as a semi-autobiographical seaside panorama unabashedly steeped in the legacies of AMARCORD and I VITELLONI. Like Kenneth Branagh’s masterful BELFAST, this is about life as seen through the eyes of a child. It’s the fleeting joys of a well-executed soccer goal, the sobering, matter-of-fact deaths of family members, and, of course, sex presented as both ineffable fantasy and anticlimactic reality.

The maraschino cherry on top is that THE HAND OF GOD is all filtered through an impossibly gorgeous travelogue lens that might recall the Italy of CALL ME BY YOUR NAME. In fact, Filippo Scotti’s authentic performance here struck me as a down-to-earth response to Timothee Chalamet’s well-sanded demeanor in Guadagnino’s film. From the moment Sorrentino presents us with the opening helicopter shot of the sea and the town we are about to cinematically inhabit for over two hours, we unequivocally know that what we are about to experience is something that screams to be seen on a large cinemascope screen to observe every detail. After all, Sorrentino is a man who strictly makes capital-F Films (even when he’s making television like THE YOUNG POPE). Quite a rare thing when shooting lazy, close-up TV coverage ideally composed for a laptop screen seems to be the norm in the era of Netflix, an era which ironically also allows for a film such as this to even be widely seen in the first place. It’s hard to talk about a film so subjective, but I’ll leave it at this: the puckish smile on the always delightful Toni Servillo’s face is as life-affirming as the film itself. The whole effervescent endeavor is ideally experienced on a warm summer evening with a Campari and Soda in hand, and a nostalgic disposition in mind. [Reid Antin]

17. THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD

Director: Joachim Trier

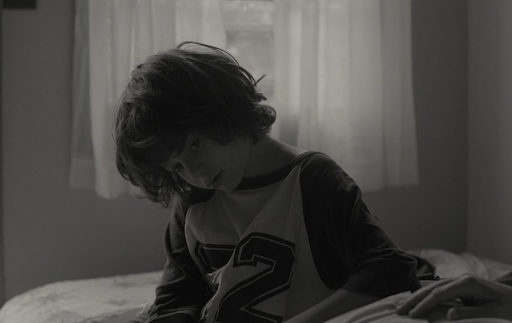

In her “Living” series, Jenny Holzer wrote: “There is a period when it is clear that you have gone wrong but you continue. Sometimes there is a luxurious amount of time before anything bad happens.” THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD exists in the continuation, in the (sometimes not so) luxurious amount of time before anything bad happens. Everything in Julie’s life is okay, but not really. It’s fine, but it’s the worst. We follow Julie from 20-something-hood, armed with a bright future ahead of her and a million silly decisions to make, into 30. And it’s at 30 when that luxurious time comes to an end. That sticky period, when you’re still allowed to be a hormone-driven fool not-cheating on your 44-year-old boyfriend with a hot stranger at a party you crashed, but that hangover, physical and emotional, starts hitting a lot faster and a lot harder than before. Joachim Trier’s 12-chapter saga investigates the fragility of relationships– be they romantic, platonic, familial, or with oneself. No matter how funny or romantic or emotional every sequence feels, there’s an underlying tension; an understanding that with one word, everything could crumble. And why shouldn’t it? Trier masters the traditional romantic comedy balance of a picture-perfect ending with everything working out just so, while our main character kind of does whatever they want without any acknowledgement of the consequences. And then he takes a sledgehammer and busts through it.

In the way that THE MATRIX: RESURRECTIONS sort of makes fun of its audience for wanting to watch it, THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD certainly wants you to feel silly for yearning for a happy ending. So much of the responsibility of the film rests on Renate Reinsve’s shoulders in her performance as Julie—passive, as she watches her life happen to her, but her eyes lit with the fuse of an uncertainly timed bomb. It almost feels ridiculous to write about the best facets of THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD because so much of its greatness lies in the viewer’s own proximity to 30. Maggie Nelson once wrote, “we sometimes weep in front of a mirror not to inflame self-pity, but because we want to feel witnessed in our despair.” In 2021, THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD might just be the Hall of Mirrors. [Aya Lehman]

16. WEST SIDE STORY

Director: Steven Spielberg

Although this is Steven Spielberg’s first foray into directing musicals, in many ways it feels as though his whole career was leading up to this moment. Rather than the choppy edit seen in most modern movie musicals, from CHICAGO to CATS, Spielberg’s signature style sweeps us in one seamless motion through the New York City streets, allowing us to take in all the beauty and grit; it’s the perfect backdrop to a miraculous ensemble of Broadway faces waiting to take Hollywood by storm. If you are a fan of the 1961 original, or the award-winning stage production, much of WEST SIDE STORY will fan the flames of nostalgia, from the Jets snapping and striding across the pavement, to Maria’s iconic white dress from the gymnasium mixer. However, Spielberg’s take has a greater sense of danger, of stakes, and restlessness. Scenes with the Puerto Rican “Sharks” have more empathy and authenticity woven in, as Spanish language and culture are highlighted throughout, without subtitles, to immerse us in their New York City. These intentional touches enhance the storytelling and ground it in a more relatable place; anyone who doubted the purpose of this “remake” is forced to rethink their original stance. It doesn’t feel like a remake, but rather a retelling that breathes new life into an over-told and oversaturated Shakespearean narrative. While the romance of Tony and Maria is the beating heart of the story, and Rachel Zegler especially shines in her star-making role, it’s the multi-dimensional and emotional performances given by supporting cast members Mike Faist (Riff), Ariana DeBose (Anita), and David Alvarez (Bernardo) that color this film with a greater emotional depth than the original. [Lauren Chouinard]

15. THE LOST DAUGHTER

Director: Maggie Gyllenhaal

After watching THE LOST DAUGHTER with my mother, she told me she’d once read a parenting column in which the letter-writer thanked the columnist for telling her readers that they are not bad moms for having fallen asleep while playing with their kids, and that it’s only natural to reach such a level of exhaustion when caring for another human. Maybe, if THE LOST DAUGHTER’s Leda had someone to tell her this, we wouldn’t be here right now. It’s not that Leda is a bad mom, it’s that she wasn’t really meant to be a mom. The confines of heteronormativity and gender conformity closed in on her at a young age—having had her daughters at, what, 23? She insists she can’t raise them. She insists she hates talking to them on the phone. And no one listens to her. Because she’s a woman, wasn’t she born to do exactly this?

With THE LOST DAUGHTER, Maggie Gyllenhaal takes a 73-page novella and transforms it into an intense, two-hour character study of a strange and angry woman, and a deep-dive into the generational trauma that’s intrinsically linked to the cycle of motherhood. It’s silly to say that Olivia Colman delivers a career-best performance when every performance she delivers is career-best, in that she continually finds new corners to reach with every choice she makes, but her turn as Leda is so mesmerizing, and makes it impossible to write the character off as simply selfish or uncaring. As female anti-heroes make their way into the mainstream, there’s simply no one leading the charge like Olivia Colman, CBE. Shocking that this is Maggie Gyllenhaal’s directorial debut, as THE LOST DAUGHTER is so confident in its undertaking, yet laid back in its presentation of such an impervious subject matter. Gyllenhaal has this gorgeous skill of making every character simultaneously someone you’d hope to never encounter, but also… Kind of want to get drinks with. Maggie’s boys are sexy, her women are exactly the sort you hope to get stuck next to at the nail salon, and her kids are the most annoying creatures on earth. Fuck them kids, THE LOST DAUGHTER rules. [Aya Lehman]

14. BAD TRIP

Director: Kitao Sakurai

Imagine if Jonathan Demme made BAD GRANDPA and you’ve got BAD TRIP. Kitao Sakurai’s wild blending of road trip comedy and Eric Andre’s public stunts scaring normal, unsuspecting people transcends both modes of humor into a richly layered, pop-friendly experiment. The cliché antics of early 2000s buddy comedies are played out amongst strangers who don’t realize they’ve been thrown into a sociological experiment, and Sakurai centers their earnest reactions as the heart of the piece. Some folks cannot believe what they’re seeing, laughing it off or trying to distance themselves as much as possible. Even more magical is when people feel compelled to step in and “help.” Eric Andre, Lil Rel Howery, and Tiffany Haddish (who particularly impresses with their daring nature and everlasting charisma) are quick-witted and incredibly brave in curating improv comedy scenes where most of the improvisers are unwitting. While sarcastic about the by-the-book moments playing out in real life, the cast is affable and tender, often for the sake of pulling similar reactions from their subjects. At its best moments, BAD TRIP manages to paint a portrait of humanity that’s driven by patience, empathetic benefit of the doubt, and humor. It mines a gleefully humanist edge out of what could be simply cruel. The production behind such an endeavor is understated and deeply creative, always lining up as many “interactive” occurrences along the narrative’s progressing beats. What’s magical about BAD TRIP is that the energy emanating from the end credit bloopers’ magical moments of relief and catharsis actually manages to radiate throughout the entire picture. If there’s ever a movie from the COVID era that fully deserves a future theatrical revival, consider BAD TRIP among them. [Rocky Pajarito]

13. OLD

Director: M. Night Shyamalan

Despite the mountains of negative reviews and numerous misperceptions about his work, M. Night Shyamalan still staunchly refuses to dilute or sacrifice the deeply idiosyncratic, unabashedly earnest filmmaking style he has developed over the past 20 years. His latest thriller, OLD, is arguably the peak of his career thus far—a testament to his strengths as both a storyteller and a visual stylist. There is a simple terror in experiencing your body and mind deteriorate with age, and the film milks that fear for all its worth. The collapse of normal time allows for a great amount of experimentation on Shyamalan’s part, where he can condense the turbulence of a decades-long marriage into the span of a day and transform minor illnesses into horrific afflictions. Shyamalan has an almost unparalleled skill and efficiency at structuring these kinds of thrillers, seamlessly building up the stakes and establishing the dynamics between characters. The film is littered with jaw-dropping compositions and incredible camera movements. Much of the horror of OLD comes from the copious amount of reaction shots Shyamalan and Gioulakis include that close in on a character’s facial expression, perfectly capturing their fear and terror. One particular sequence that has been stuck in my mind for months is of the kids playing freeze-tag, where the camera races around the actors and suddenly stops with them as they are tagged, zooming in and out all the while. The shot is not only stunning to look at but feels radically aligned with the children’s point of view as they run around with each other on the sand. Even though the ending “twist” of OLD is perhaps its weakest part, it cannot detract from the tender last moments between Bernal and Krieps as they reconcile before dying or the raw, triumphant catharsis of the film’s final moments. [Ethan Cartwright]

12. C’MON, C’MON

Director: Mike Mills

Director Mike Mills is a master of creating films with a deep emotional core, that invite both his characters and his audience to reflect deeply on their connection to family in all its messy forms. Although C’MON C’MON is a stylistic departure from his more colorful filmography, the film’s earnest tone marks it as his most sincere yet. It’s nearly impossible to get through the film without at least one big smile on your face and a tear in your eye. The chemistry between Phoenix’s Johnny and the young Woody Norman’s Jesse is electric, as you watch Johnny grapple with a newfound protectiveness over his inquisitive nephew, stumbling over his parental role with as much patience and understanding as he can. It’s been a few years since I’ve gotten to see Joaquin Phoenix in a quieter, more subdued role, and I didn’t realize just how much I missed this side of him. Phoenix is at his best when he’s deep into these roles where he grapples with the philosophical and the vulnerable, where he can explore the power of 1:1 connection while juxtaposed to a fast-paced world surrounding him. These kinds of roles where he plays a man trying to make the best of a hard situation may not be enough to get him awards attention, but they certainly demonstrate why he is one of the smartest working actors today. We’re all out here doing our best, trying to connect, trying to hold onto each other gently through unspeakable hardships. Like a tender touch on the shoulder that says “everything is going to be okay,” C’MON C’MON is the cathartic reminder that grief and joy can exist as one. [Lauren Chouinard]

11. PIG

Director: Michael Sarnoski

PIG, from the title to the plot to the casting, felt destined to live more as a meme than as an actual film—such is the heavy burden of casting Nicolas Cage in a revenge movie about pigs set in the Portland restaurant scene. Filled with underground fight clubs and vengeful truffle traders, when you describe the moments of action in director Michael Sarnoski’s script out loud, it all feels remarkably like the throwaway straight-to-DVD fodder that Cage has been cashing paychecks on for the last decade. And while the internet’s labeling of PIG as “JOHN WICK meets RATATOUILLE” is cheekily accurate in some ways, it doesn’t quite capture the quiet loneliness that permeates. The camera frequently rests on Cage’s weathered, tired face, finding wisdom and pain where other directors have found a mania and intensity—the largely silent performance subverts that polarizing and erratic spontaneity into a lumbering profundity, making the moments of tension and violence even more jarring. Even if it will undoubtedly be followed by four or five unmemorable Cage roles, PIG gets the most out of the veteran actor. [CJ Simonson]

10. THE BEATLES: GET BACK

Director: Peter Jackson

The decades since the Beatles broke up have been filled with an overabundance of personal histories, critical analyses, and cultural texts that try—in varying degrees—to speak on the artistry and sheer phenomenon The Fab Four had and continue to have. The beauty of Peter Jackson’s THE BEATLES: GET BACK is that it lets John, Paul, George, Ringo speak for themselves. Though the Beatles would not split until a year later, the timespan the documentary covers feels like the beginning of the end. So many crises proliferate around the edge. The frustrations and disagreements that have built up between the four; the underriding fear of having plateaued artistically; uncertainty about whether there is anywhere left to go after being at the top; the conflict between staying with your friends and wanting to create independently. These tensions rarely manifest in nasty arguments. Jackson wisely abstains from dealing with these issues directly–in part to avoid repeating footage of the original 1970 documentary, LET IT BE, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, a prominent side character in Jackson’s edit. The result is simply magical: eight hours of watching the band work together alongside girlfriends, wives, producers, and recording staff as they go over classic songs like “Two of Us” and “Let It Be,” or play around with other contemporary hits. There are an incredible number of moments that we are so lucky to have captured on film, from Paul coming up with “Get Back” almost out of thin air to George walking on set one day and talking about how he couldn’t stop thinking about the phrase “I Me Me Mine” while watching late-night television. One day, keyboardist Billy Preston shows up while the Beatles are recording, and the band eagerly recruits him to stay in London and rehearse with them for a couple weeks. The famous, climactic rooftop concert is splendidly compiled; Jackson’s use of splitscreen simultaneously shows the band, the gathering street-level crowd, and the Metropolitan Police fecklessly attempting to stop the public disruption. The digital restoration techniques have been (rightly) criticized, but the pitch-perfect structure of the documentary combined with the sheer power of the footage itself overpower any misgivings about the uncanny smoothness. That we are able to see this “new” footage after it spent 50 years hidden away is one of the genuine miracles of 2021. [Ethan Cartwright]

9. TITANE

Director: Julia Ducournau

In only two features, Palme d’Or recipient and new age horror master Julia Ducournau has workshopped a foolproof recipe for wringing her audience like wet laundry. A daughter of doctors, her sophomore effort, TITANE, treats the vigorous biting and near-ripping of a nipple piercing as an aperitif for the biological traumas to come. The hits start early, and they don’t stop. There’s a sick entertainment in seeing what, if anything, can make Agathe feel a shred of painful humility; if the Red Scare chick made a movie about how she perceives everyone else’s perception of the world, then Julia Ducournau made a movie about the distanced psychosis of being Dasha Nekrasova.

Instead of slicing through cables and having little rodent servants bite on the frayed exposure like Cronenberg does, the gonzo godfather she’s often compared to, she chews on the cord herself. What exactly is TITANE saying about trans identities? Is it even? Are we all prone to murder? And are we all capable of finding love in wicked deposits if we’re cornered into our darkest depths? The film’s overwrought, and downright gorgeous, compositions are facades for a movie that never knows what it is or what it’s about. Like its protagonist who fails upwards until she, arguably, fails in a flesh-ripping spiral, TITANE is following the bare scent of a vibe as it goes along. You want it to coagulate into a central thesis? That’s your job. Perhaps living as Adrien grants Agathe the absent father figure she never made peace with, or maybe masculine gender performance is merely a costume of anonymity wherein anyone who dons it is assured the normalization of apathetic psychopathy. Boys will be boys. Ducournau’s worlds concern themselves with the affected and those to soon be affected, because cinema was designed to watch people do things and things happen to people. Whether you’re one to find personal sanctuary in the Almodovar-indebted emotional compromises, or your offended sensibilities unleash the frustrated “What’s the point?” hammer, both of you will end up looking stupid trying to play hall monitor on a Euro-splatterpunk-erotic-mystery-science-fiction slasher. [Kevin Cookman]

8. THE MATRIX RESURRECTIONS

Director: Lana Wachowski

What happens when you make the most widely influential work of trans cinema… before you figure out you’re trans? That Lana Wachowski was able to contemplate this to the tune of nearly $200 million is worth appreciating on its own, no matter how you felt about THE MATRIX: RESURRECTIONS. The result is an angry, triumphant, thoughtful, and deeply, deeply personal conclusion to one of the greatest sci-fi sagas. RESURRECTIONS not only acknowledges the subtext of the original, but seizes the opportunity to integrate a modern understanding of trans existence. The big beautiful cherry on top is Bugs, a constant delight and stand-in for every trans person who recognized themselves in the original trilogy. Neo’s engagement with Bugs and crew, realizing that his creation helped them wake up from The Matrix and now they’ve come to help him and Trinity, warms the cockles so thoroughly you could roast a marshmallow over them. It’s such a surprising textual treatment of fandom in a media landscape where disgruntled auteurs complain about Redditors guessing season three twists. Instead, RESURRECTIONS celebrates its trans fanbase being 10 steps ahead of its creators and puts them in the driver’s seat for their own special adventure with Neo. Its indictment of Hollywood executives is so acidic it could strip paint off a car. It marches up to the alt-right fuckheads who have turned “taking the red pill” into a call to action and declares, unambiguously, that this franchise is not for them and never has been. It’s a dizzying turducken of self-hatred and self-awareness, going so far as to include multiple minutes of the original 1999 THE MATRIX; while it’s remaking the opening of the THE MATRIX; while two characters in the movie are watching and critiquing the remake of the opening of the THE MATRIX. RESURRECTIONS looks you right in the face and sneers. Neo/Thomas Anderson canonically rebooting The Matrix is a traumatic experience that sends him tumbling back down the rabbit hole all over again.

RESURRECTIONS is a level of raw emotional honesty about painful art that feels unprecedented in a modern blockbuster fourthquel rather than, say, a microbudget Netflix comedy special that also came out this year but “isn’t technically a film” so it’s “not eligible” for this list. (Hey, can’t the blurb about the most meta movie of the year also be meta?) THE MATRIX: RESURRECTIONS is undeniably shaped by going on without the people you depend on. Lana came back to the franchise without her sister Lilly, master cinematographer Bill Pope, and the incredible principal stunt team of Woo-Ping Yuen, Glenn Boswell, and Chad Stahelski (though Stahelski has a fantastic cameo). THE MATRIX is action-packed, but it was never about action, and RESURRECTIONS declines the opportunity to cloak its real meaning in splashy setpieces. After all the snarky in-joking, it ends with Neo and Trinity flying off together to fix the broken world. It sends a message that becoming who you are opens you up to truly love and be loved by someone else. What could be a better cap off to a year of trickery, disappointment, and bullshit? You did it, Lana. [Kate Brogden]

7. SPENCER

Director: Pablo Larraín

I think most thought the Diana Spencer well had run dry. I am not a Royals person, and I’m not partial to any of them as celebrities or dignitaries—they’re hyper-wealthy mannequins stuck in arrested development. With that perspective, paired with a year living with my parents as a 30-year-old married woman, at their home, on their terms, during a pandemic, SPENCER shook me to my core. It found me when I was weak, when I too was at my mental breaking point as a woman without agency and with immense privilege. Pablo Larraín masterfully spins this fable as a piece of psychological horror. He attempts to climb inside the labyrinth of Diana’s unstable mind as she grows increasingly delusional and self-important. I understand the disdain people feel when observing this sort of pathetic pop icon. Most films and stories of celebrity addiction or mental illness are told with an earnestness, and sometimes exploitative view, almost as if it’s an endearing character quirk. Larraín bashes this pearly facade with an anvil. He doesn’t treat his protagonist lightly, and doesn’t forgive what occurs. The only glamorizing is in the eye of the beholder. Kristen Stewart absolutely nails a manic, skittish Diana spiraling into an increasingly surreal, nigh-suicidal state. It’s truly a brutal film. Stewart’s physical acting is perfection, massaging her naturally restive movement for a softer, but equally disconcerting body language. She is bound to the hand that feeds her–no matter how expensive the setting or the clothes, it is all too overwhelming. The lack of personal space, adherence to rules that don’t make sense… It all wears you down. Imagine living in a never-ending cycle of holiday meals with the relatives you tolerate and abandoning any sense of personal empowerment. Your mother-in-law and her keepers continue to take notes of your eating disorder, your minor transgressions from the schedule she expects you on… Seriously chilling. [Hilary Jane Smith]

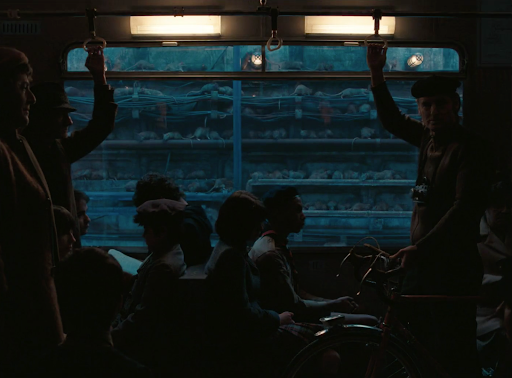

6. DRIVE MY CAR

Director: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Driving offers space to think. It’s a mundane activity to the point that you can forget you’re doing it while you do it. Veteran actor/director Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) uses driving to rehearse, to stew over his wife Oto’s (Reika Kirishima) affair, and eventually to share in the grief over Oto’s death with the unlikely friend he finds in his driver Misaki Watari (Toko Miura). It’s also the logic Ryusuke Hamaguchi applies to all of DRIVE MY CAR. Every scene offers space, enough nooks and crannies for performance and meaning to hide. It’s really to his credit that even though his Haruki Murakami adaptation feels long and impossibly slow, it’s never uninteresting. Kafuku’s study of translation, performing Chekhov’s UNCLE VANYA in multiple languages at the same time, seems to be about finding meaning beyond meaning. He wants his actors to understand the timing of conversations rather than their content––much to their frustration and confusion––while he struggles to understand why his wife was the way she was. Maybe there’s nothing to be learned, no secret to her extramarital affair beyond the fact it happened. Maybe Kafuku, or the strange ally he finds in his wife’s younger lover Koji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada), can never understand her. Hamaguchi finds beauty in not knowing, shooting actors in scenic, and melancholic Hiroshima landscapes. Even with a lifetime’s worth of long drives, some things never resolve. There’s a power in stopping, collecting yourself, and deciding to drive on anyway. Minding your blind spots, literal and figurative, but not letting what you can’t see, can’t know, leave you driving in circles. [Ian Campbell]

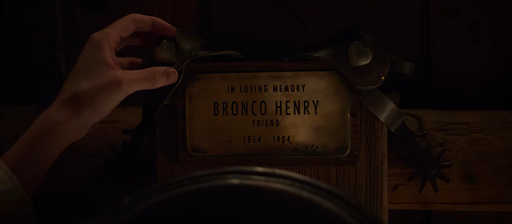

5. THE POWER OF THE DOG

Director: Jane Campion

Besides being an amazing stand-in for Montana—New Zealand is a more beautiful terrain than the United States could ever produce—Jane Campion’s decision to have her home country act in her adaptation of THE POWER OF THE DOG represents a core tension of the film on the largest scale possible. Almost every person on the Burbank ranch is trying to live a life that’s not their own. Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch), the alternatingly creeping and stomping villain of the film, is haunted by his “mentor” Bronco Henry, donning a mantle of toxic masculinity that only violence can undo. Rose Gordon (Kirsten Dunst) falls in love and fails to stifle the anxiety caused by being thrust into an entirely new social strata. And George Burbank, the softer side of the Burbank clan, views his marriage as some kind of escape from his brother’s metaphysical death spiral. Only Rose’s son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) seems to fully be himself, and Campion’s hypnotic waltz through his slow dissection of the lives on the ranch is what pulls everything together. If pretending to be something you’re not is the sickness, then seeing, really seeing things for what they are, is the medicine. What’s so compelling about THE POWER OF THE DOG is all the ways Campion illustrates that, in close-ups, inserts, and hillside shadows. Is Phil getting close to Peter because he sees it as a way to get back at Rose, or because he finds a kindred spirit in him? Is Peter showing interest in Phil’s work because he’s genuinely curious, or because he’s found a way to destroy him? In Campion’s film, it’s all four at once, and impossible to look away from, whichever way you spin it. [Ian Campbell]

4. RED ROCKET

Director: Sean Baker

America is powered by delusional people. The mirage of The American Dream propels people forward in spite of all evidence that it’s time to give it up. Sean Baker’s RED ROCKET centers on a deeply delusional and deeply American man, Mikey Saber, a porn star and suitcase pimp who believes his own bullshit too much for his own good. The motor-mouthed motherfucker is objectively a monster, but even after one of his most shocking and brazen acts, Baker manages to make you desperate to see Mikey wriggle his way out of facing the music, and then instantly makes you culpable for cheering him on. The male fantasies Mikey peddles might be paper thin, but he believes in them so resolutely that he’s impervious to anything fate might throw at him. He’s an anti-hero incapable of feeling shame, and in America that’s enough to make you unstoppable. Much like watching actual porn, RED ROCKET can make you feel dirty and compromised after you finish, but the lasting effect defines one of the most compelling films of the year, a vivid portrait of an abuser and how he gets away with it. Gorgeously shot with a skeleton crew for almost no money in 2020, Red Rocket is stubborn proof that great films are possible as we continue to live through the pandemic. Baker’s craft and autuership only get sharper and more fascinating as he and his crew of collaborators refine their techniques. His ability to blend seasoned actors with found talent remains unparalleled, Suzanna Sonn is a star in the making, and Ethan Darbonne and Brittney Rodriguez have promising careers ahead of them if Hollywood has any sense at all. Baker remains one of the most vital directors in contemporary American cinema; no one else is looking into the marginalized lives of sex workers with such empathy, and reflecting our broader culture back to us with shocking clarity in the process. [Carter Moon]

3. BENEDETTA

Director: Paul Verhoeven

To say that a film by Paul Verhoeven is ahead of its time is to say that it is right on time. Whether you want to call it divine intervention, genius, or something else entirely, the filmmaker has been creating satirical visions of societal ills before they come to mass fruition, as he did for clout-chasing in the digital pop culture era with SHOWGIRLS (1995), the Iraq war with STARSHIP TROOPERS (1997), the hyper-militarization of American police forces with ROBOCOP (1987), and has done again for cancel culture in the midst of a pandemic with BENEDETTA. As provocative as it is prescient, and bitingly funny to boot, the film examines who gets to decipher the word of God in a world where the word of God is law, and how that is inseparable from the secular, fiscal realm. “This is a convent, not a charity,” the Reverend Mother explains in deadpan to poor runaway Bartolomea (the strikingly beautiful Daphne Patakia reminds you of an Instagram-era Liv Ullmann), as she begs to be brought into the convent and saved from her abusive father. “You have to pay to be here.” To Benedetta, both her sexuality and her violent outbursts are an extension of her spirituality—her beautifully violent Buñuelian visions of Jesus and her romantic connection to Bartolomea are the ways she expresses her core connection to her God. In classic Verhoeven fashion, he’s curious about Benedetta’s spiritual confluence between sex, violence, and religion. Verhoeven isn’t just including these elements for the sake of shocking the audience. This isn’t exploitation. At the same time, Verhoeven is of course aware of his images’ capacity to offend and titillate, and he knows that it rules. Remember when the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family, and Property protested the film for its blasphemy outside of Alice Tully Hall during NYFF? If that wasn’t a clear sign from God that BENEDETTA is one of the best films of 2021, then I’m not sure what is. [Katarina Docalovich]

2. THE FRENCH DISPATCH

Director: Wes Anderson

Folks, must we beg Wes Anderson to stop being Wes Anderson? We’ve only got one Wes Anderson as it is, and we should celebrate when he stretches his vision into towering, manic structural experimentations like THE FRENCH DISPATCH. The ways in which he expands his palette is practically a gift, considering how few majorly released comedies boast the kind of imagination and intricacies Anderson considers for split seconds of his affairs. As frantic and constantly changing as this film is, Anderson continues his streak of letting all his films breathe and bleed with melancholy. Look deeper into all of the quirks that are indeed overwhelming and indulgent and one should feel a deep sense of loneliness, and the mixed emotions that come with hope throughout THE FRENCH DISPATCH. His ensemble is perhaps at its biggest it’s been yet, with everyone firing on all cylinders, eager to help create the massive miniature art-piece Anderson desires to make.

THE FRENCH DISPATCH is about dreamers realizing the impenetrable walls that grow in the distance ahead of them, be it age or futility of ambition. The haphazard nature of the structure is not only aesthetically dizzying, bouncing around various framing devices while keeping them all in sync, but it still manages to pull together coherent emotionality for its rotating cast, peeking into their hearts through their words and works alike. For all the symmetry and bombast, he continues to pull his characters and audiences into places of wisdom in the face of eternal grief. His particular brand of grace can be powerful if given more sight than “lol it’s so twee.” Like what you like and don’t like what you don’t, but it’s really hard to deny that even in a purely stylistic sense, Anderson’s vision is mutating and evolving here. The speed at which gags and action are flung about here is impeccably handled, like an orchestrator simultaneously performing jazz drum solos. In motion, it feels like actual movie magic, which feels like a crime to shrug off. His perspective may be limited, which has always been an issue with his work, but the ways in which he can break open the medium of visual storytelling proves that he’s not done innovating, and we should not be done learning and iterating. Anderson is mastering a version of this craft that is his and his alone, building dedicated and intelligent teams of artists to bring life to the deeply unique like nearly no one else can. THE FRENCH DISPATCH is big and all over the place, and a welcome and wild addition to his tidy filmography. [Rocky Pajarito]

Listen to our full review here.

1. LICORICE PIZZA

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

LICORICE PIZZA is a document of effortless, uncomplicated love. A pure, rapturous first love, the kind you have no choice but to reach out and grab with both hands once you find it. As far as I’m concerned, any age gap discourse surrounding this movie is either Twitter bait coming from unfeeling nerds desperate to score bad-faith woke points, or manufactured by the government to make me personally go insane, or both. LICORICE PIZZA is yearning for the one person you can’t have, it’s knees and fingers innocently brushing against each other, it’s butterflies in your stomach when you see your crush across the room in spite of yourself. Gary tells his younger brother Greg that he’ll marry Alana one day, while Alana wonders aloud to her sister if it’s “weird that she hangs out with Gary and his 15-year-old friends all the time,” despite making little effort to stop hanging out with Gary and his 15-year-old friends all the time. There’s no will they/won’t they, never a doubt that they will surmount the low stakes obstacles in the way of their romance. Yearning lies at the heart of many of Paul Thomas Anderson’s films; often, romance succeeds (or fails) in spite of a seedy underbelly. Alma and Reynolds’ love overcomes their dueling, domineering personalities in PHANTOM THREAD, while Shasta and Doc’s romance is ultimately squashed by the deep state in INHERENT VICE (which of course doesn’t make it any less meaningful). LICORICE PIZZA can be set apart from many of PTA’s other films in its wholesome lack of malicious undercurrent; it’s a “loss of innocence,” without the loss. With Gary and Alana, the wanting is more interesting than the having–their awkward journey to romance is more important than the destination. [Katarina Docalovich]

Comments